“Time is short!” is a maxim often repeated by military planners. It was similarly intoned by the planners and organizers of the World War II Memorial on the National Mall.

2019 marked the 15th anniversary of Memorial’s dedication. While there had long been consensus on the need for a national memorial in Washington, DC to commemorate America’s victory in World War II, the initial progress was slow. Yet the WW II veterans were aging. As most WWII veterans were entering their late 60’s or 70s, there was a growing concern within the broader veteran community about the need to build a memorial before that generation passed away.

Congressional legislation authorizing the project stalled several times, finally passing in 1993. Once signed into law, an advisory board was formed, a sight selected, funds raised, designs submitted and construction begun.

The image of Nike, from the World War II Victory Medal, under the Atlantic and Pacific pavilions at the World War II Memorial

Finally, on May 29, 2004, as part of the largest reunion of US World War II veterans, President George W. Bush dedicated the World War II Memorial. In his speech that day, President Bush remarked that winning the war “would require the commitment and effort of our entire nation. To fight and win on two fronts, Americans had to work and save and ration and sacrifice as never before”.

The memorial, over ten years in the making, honors that two front victory, that commitment, that sacrifice and the unity of the American people who achieved it. That honor is reflected in part by the memorial’s location, on the National Mall between the Washington Monument and the Reflecting Pool, with the Lincoln Memorial appearing in the distance. The location signifies how the struggle to win World War II is comparable with the contributions of Lincoln and Washington in American history.

Approaching from its 17th Street entrance, the memorial greets you, a broad expanse of granite, water and metal. It can be confusing at first. Its neoclassical design incorporates a jumble of names, figures, and symbols. But slowly, the imagery becomes cohesive and themes emerge — victory of course, but also unity and reverence.

The visitor’s eyes are first drawn to the oval shaped Rainbow Pool with its twin fountains. This feature was originally designed in 1923 by Frederick Law Olmstead and was part of the National Mall for many decades. It was later incorporated into the World War II Memorial’s design. Arranged in a semi-circle around the pool are 56 granite columns, one for each US state and territorial possession during World War II. Alternating victory laurels of wheat and oak leaves (signifying agricultural plenty and industrial capacity respectively) adorn each column while a bronze rope, indicating unity, ties the columns together.

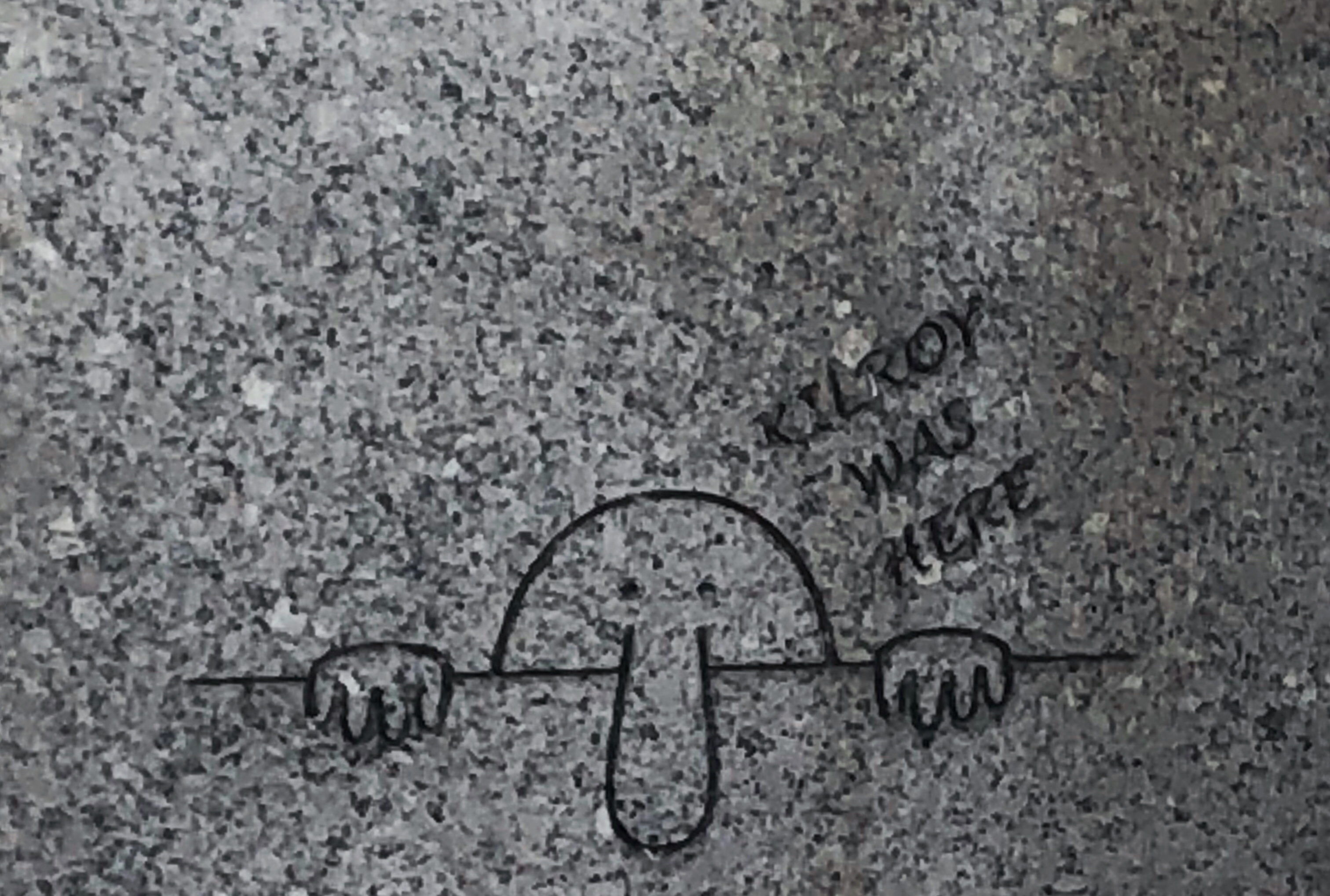

On each end of the pool are two 43-foot-tall pavilions, representing the victories in the Atlantic and Pacific theaters. Major campaigns and battles of each theater are inscribed at the base of the pavilions. Four stately bronze eagles, one for each branch of the US Armed Forces are perched inside. They hold aloft a large victory wreath representing how the combined efforts of the armed forces secured victory on the land, on the sea and in the air. On the pavilion’s floor is a bronze disk with an image of the Greek goddess Nike, the same image depicted on the World War II victory medal issued to US service members after the war.

Aligned along the entry walkway are two series of bronze bass relief plaques rendering period images from the World War II era. Scenes from the war in Europe are found on the north side, aligned to the Atlantic Pavilion. Scenes from the Pacific are found on the south side, aligned to the Pacific Pavilion. Depictions from both the battlefront and home front are included, showing the unity of the American people in the war effort. The last two plaques denote victory — U.S. and Russian soldiers linking up in Europe and civilians celebrating the end of the war in the Pacific.

While the memorial is meant to honor the 16 million Americans who served in World War II, there is a special section to honor the approximately 400,000 American servicemen and woman who died during the war. The Remembrance Wall on the western edge of the memorial is composed of over 4,048 gold stars on a blue background, each gold star representing 100 fallen service members. On either side of the Remembrance Wall are two small waterfalls which, along with the Rainbow Pool’s fountains, muffle the sounds of the many boisterous pedestrians, vehicles and overhead aircraft transiting the area. The cascading waters allow for quiet contemplation before this visual reminder of the price of war.

Naturally, the process to build the memorial was not without some contention. While there was a sense of urgency among some, there were also objections raised to the memorial’s prominent location on the National Mall, its design, and the accelerated approval and construction timeline. (Congress exempted the World War II Memorial from certain legal requirements other groups needed to follow out of concern for the aging World War II veterans.) Despite these controversies, today the World War II Memorial is one of Washington’s most visited sites. The National Park Service estimates the memorial drew about 4.8 million people in 2018.

A bouquet left at the memorial in memory of a World War II veteran.

The memorial has even spawned a nationwide organization known as the Honor Flight Network, dedicated to transporting veterans from around the country to Washington DC to see those memorials dedicated to their service and sacrifice. Since 2005, the Honor Flight Network has transported over 220,000 veterans, along with 163,000 escorts, to Washington. The memorial draws many other organized visits by veterans groups and survivors organizations leading to emotional reunions and the presentations of long overdue awards such as this one recently recounted in the Washington Post. Events such as this, as well as the many wreathes, flowers, notes, pictures, and other mementoes left at the Memorial are testament to its effect as being a meaningful tribute to the legacy of our WWII generation.

* * *

Computer Registry

Adjoining the Memorial is a small National Park Service building with computer kiosks where the visitors can access the Registry of Remembrances, an unofficial compilation of names, units and events entered by members of the public to honor US service members who helped to win the Second World War. More information on the registry and how to enter information about someone you know can be found here.

Route Recon

The World War II Memorial is located at 1750 Independence Ave. SW, Washington, D.C., near the intersection of 17th Street and Independence Avenue. Very limited parking is available on West Basin Drive, on Ohio Drive SW, and at the Tidal Basin parking lot along Maine Ave., SW.

A better option to access the National Mall is the Washington Metro System. The nearest station for the World War II Memorial as well as the Washington Monument is Smithsonian Station. Use the Mall Exit when leaving the station.