In a city abundant with statues, monuments and memorials, a few stand out for their uniqueness. One of these sits to the northwest of the US Capitol in the middle of a traffic circle formed where Pennsylvania Avenue terminates at First Street, NW. It is one of three pieces of statuary, along with memorials to Ulysses S. Grant and James Garfield, that form a visual connection between the US Capitol Grounds and the National Mall.

Dedicated to the sailors and Marines who died during the Civil War, the statue is known as the Navy Monument or Peace Monument. Unlike its neighboring statues which feature American statesmen cast in bronze, the Peace Monument mixes a variety of classical figures arrayed around an upright bloc, all captured in Italian marble.

At the top of the 44 foot high monument are two robed figures facing the National Mall to the west. One is Grief, who buries her head in one hand, while resting her other on the shoulder of History, who stands bearing a pen and scroll inscribed with the words: They died that their country might live.

Midway down the monument, Victory holds her laurel high in her right hand, while a very young Mars (the god of war) and Neptune (the god of the sea) sit at her feet.

On the reverse side of the statue, the figure of Peace looks towards the US Capitol. At her feet are a collection of items symbolic of the benefits of peace. There is a cornucopia and a sickle representing agricultural bounty while a gear and a book represent industry and the pursuit of knowledge.

Four large marble spheres on their own bracket-shaped pedestals are found on the corners of the monument along with classical adornments, such as wreaths, scrolling and scallop shells. Below the monument, jets of water shoot into a giant basin. On the west side an inscription reads: In memory of the Officers, Seamen and Marines of the United States Navy who fell in defence [sic] of the Union and liberty of their country, 1861–1865.

While it looks as if it might have been designed by a committee, the statue was the idea of one man: US Navy Admiral David Porter.

Admiral Porter was the scion of a distinguished naval family. His father, Commodore David Porter, was a hero of the War of 1812 and his adopted brother was David Glasgow Farragut (of “Damn the Torpedos” fame). Admiral Porter first served as a midshipman at age ten under his father. He would serve in the Navy for over sixty years.

Admiral David Dixon Porter

-Photograph by Mathew Brady, Library of Congress Collection

Porter sketched the original figures of Grief and History as early as 1865, then raised money from private sources for its construction. Porter was likely inspired by his father, who undertook a similar project. Commodore Porter commissioned a statue dedicated to the lives of six naval heroes who died fighting the Barbary Pirates in the early 19th century. At one time this statue was displayed near the US Capitol; it was ultimately moved to the US Naval Academy at Annapolis in 1860.

For his monument, Admiral Porter worked with Franklin Simmons, an accomplished sculptor known for his work in sculpting political and historical figures. Simmons carved the statues at his studio in Rome, working with another team of Italian sculptors to carve the monument’s shaft. He consulted frequently with Admiral Porter on including additional figures and embellishments.

After its unveiling, an art critic remarked, “Porter knows more about the high seas than high art.”

While that may well have been true, Porter’s conglomeration of figures and mixed symbology seems quite appropriate for a monument to the U.S. Navy during the Civil War.

Close-up of the Statue of Mars. Note the erosion on the fingers of right hand where he grips his sword, and on nose.

In April of 1861, the Navy had but 42 commissioned ships. It needed to expand quickly and it required many new and different types of vessels for the missions it now faced. Specialized ships were necessary for enforcing President Lincoln’s blockade of Southern ports, defeating the Confederate Navy in open waters, supporting US Army ground operations and patrolling interior rivers. This was also a transitional period as wooden sailing ships gave way to ironclads powered by steam.

The Navy set about a massive program of refitting current naval vessels, building new ones and acquiring civilian ships, which were converted for military use. By war’s end, the Navy had over over 600 vessels, some very distinct in design and purpose.

During the Civil War, the US Navy also rewrote doctrines focusing on flotilla operations rather than single ship actions, adopted new combat tactics, and revised its command structure.

Admiral Porter was on the forefront of some of these developments. He commanded a flotilla of ships in the Union capture of New Orleans. He transported Ulysses S. Grant’s army down the Mississippi River prior to the assault on Vicksburg. He also commanded naval forces in the attack on Fort Fisher, North Carolina. After a two-day long bombardment of the fort, Porter contributed a force of sailors and Marines to join US Army soldiers on a multi-pronged ground attack.

The Bombardment and Capture of Fort Fisher, N.C. Jany. 15th, 1865. [Published by Currier & Ives, between 1865 and 1872] Library of Congress Collection

While historians devote more attention to land campaigns and the Army’s epic battles, the Navy made significant contributions to the Union victory in the Civil War. During those years, 4,523 sailors lost their lives. The Marine Corps played their role as well, participating in some major land battles, enforcing blockades and conducting patrols along the rivers. During the Civil War, 148 Marines were killed in combat.

After his Civil War service, Porter served as the Superintendent of the US Naval Academy where he implemented a number of reforms to better prepare midshipmen to become naval officers. He originally intended the monument to be placed at Annapolis as was his father’s. However, the Secretary of the Navy at the time disagreed.

Congress though did approve of the statue being placed near the Capitol. Funds were appropriated for the construction of the monument’s platform and a basin for the fountain, which were made from Maine blue granite.

The monument was shipped in pieces to Washington in 1876. The next year, the monument was assembled and installed at its current site. The last statue of Peace was added in 1878. A formal dedication ceremony was delayed until the statue was completed. Dolphins were also to be incorporated as were bronze lamps, but these were never added and no formal dedication was ever held.

The Statue of Peace facing the US Capitol.

The statue was built of Italian Carrara marble, which unfortunately has not stood up to the weather or the pollution in Washington, DC. Erosion of the faces on different figures is clearly evident and various features have broken off. For example, the young Neptune is missing his trident.

Additionally, protestors have repeatedly climbed the Peace Monument during demonstrations on the Mall, further damaging the statues. A major restoration effort was made in 1991, where the marble was carefully cleaned, strengthened and missing pieces replaced. Similar work was conducted in 1999 and 2010.

Close up of the Statues of Grief and History. Note the erosion on History’s face and the missing pen from History’s right hand.

It is easy to be dismissive of the Peace Monument as something antiquated–or not related to peace at all–since it memorializes war dead. Indeed, the monument may not work as “high art”. But the monument’s story is compelling and offers some rich analogies to peace worth considering.

Like this monument’s creation, peace may take a long time. Peace might look different from what you expected. Peace may never be complete. Peace is fragile and needs constant tending. Peace may not be heralded with a formal ceremony, yet it exists nonetheless. Peace may flabbergast some, but it can endure.

* * *

Route Recon

The Navy Monument or Peace Monument is located within a traffic circle at the intersection of Pennsylvania Avenue and First Street, NW, to the northwest of the US Capitol building. The best way to get to the monument (and the Capitol) is by taking Metro.

Three Metro stops are within walking distance of the memorial and the Capitol:

- Union Station – Located at First Street, NW, and Massachusetts Avenue.

- Capitol South – Located at First Street between C and D Streets, SE.

- Federal Center, SW – Located at the southwest corner of Third and D Streets, SW.

Additional information on riding Metro, is available at the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority.

The DC Circulator, a public bus system with routes through Washington’s downtown area includes stops near the Memorial. Find more information about Circulator busses at www.dccirculator.com.

There is very little public parking available near the Capitol. The nearest public parking facility is at Union Station, to the north of the Capitol. Very limited metered street parking is found along the Mall to the west of the Capitol.

While most aspects of the memorial are clearly visible, one is not: silence.

While most aspects of the memorial are clearly visible, one is not: silence.

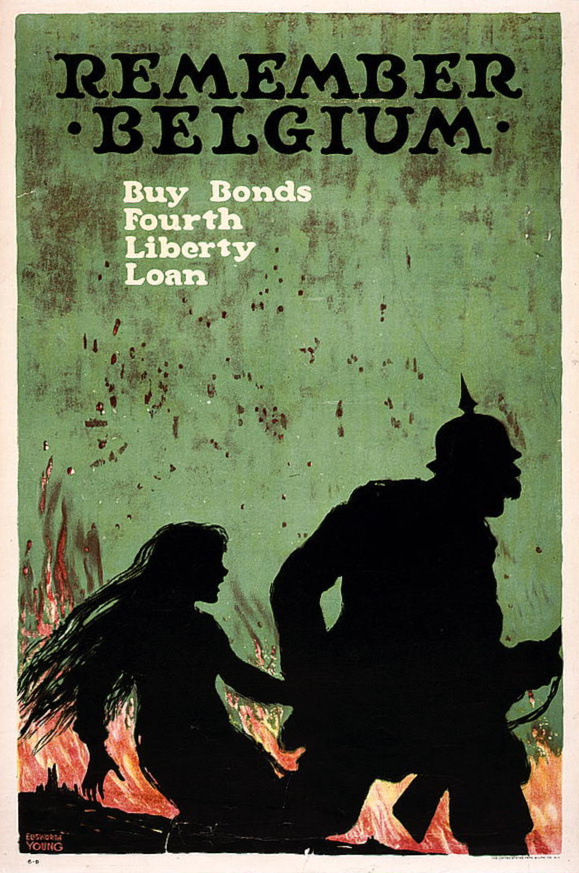

The section also highlights an important relief operation less well known today, the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB). Taking advantage of U.S. neutrality, the CRB procured, transported and distributed 11.4 billion pounds of food to 9.5 million civilians living in German-occupied Belgium and Northern France saving many from starvation. It was chaired by a young mining engineer then living in London named Herbert Hoover.

The section also highlights an important relief operation less well known today, the Commission for Relief in Belgium (CRB). Taking advantage of U.S. neutrality, the CRB procured, transported and distributed 11.4 billion pounds of food to 9.5 million civilians living in German-occupied Belgium and Northern France saving many from starvation. It was chaired by a young mining engineer then living in London named Herbert Hoover.

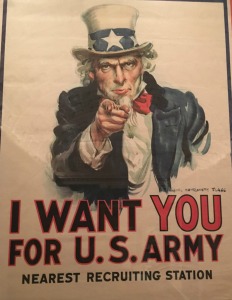

In order to preserve what is on display, some items will be rotated out every seven months so Echoes of the Great War is worth visiting more than once before its scheduled closing in January 2019. The Library of Congress also put details of the exhibit, including photos and information on what is currently on display, teaching aids, curator notes and other resources

In order to preserve what is on display, some items will be rotated out every seven months so Echoes of the Great War is worth visiting more than once before its scheduled closing in January 2019. The Library of Congress also put details of the exhibit, including photos and information on what is currently on display, teaching aids, curator notes and other resources