In 1797, President George Washington signed Commission Number 1 naming John Barry as a senior captain in the newly reconstituted United States Navy.

For Barry, it was the culmination of a very distinguished career of over 30 years as a maritime sailor, ship’s captain, naval officer and combat commander.

Today, a monument to John Barry stands on the western edge of Franklin Park in downtown Washington, DC. Passersby on busy 14th Street proceed each day under his watchful gaze, likely unaware of the man who earned the sobriquet The Father of the United States Navy.

Barry was not a native of our American shores.

He was born in County Wexford on Ireland’s southeast coast in 1745. It was a difficult time in Ireland. English penal laws limited the civil, religious and property rights of Irish Catholics.

Barry’s family was forced from their farmland when he was a young boy. He began working with his uncle, a fishing boat captain, where he developed a love for the sea. He went on to work as a cabin boy and sailor on a number of merchant vessels.

Barry settled in Philadelphia around 1760. The affluent colonial capital of Pennsylvania was a logical choice for the young mariner. It was a busy port city with a tolerance for Catholic immigrants, allowing Barry to ply his trade.

After mastering his seamanship skills, Barry was appointed a ship’s captain for the first time at the age of 21.

Barry’s stature and comportment certainly contributed to his success. At 6’4″ Barry towered over his sailors. He walked a ship’s decks with a confident, commanding stride and gave clear orders in a deep Irish brogue. His great attention to detail and technical proficiency earned him wide respect as did his reputation for taking care of his crews.

In 1775, Barry volunteered for the cause of independence from Britain. Already an experienced and highly regarded sailor, Barry was commissioned as a captain in the Continental Navy and given command of a series of warships.

He captured a number of British vessels and their cargos, providing much needed supplies for the Continental Army and Navy. His success commanding naval vessels caught the attention of the British, who offered him a Royal Navy commission and a hefty bribe to leave the Continental Navy.

He promptly refused.

A portrait of John Barry painted by Gilbert Stuart in 1801.

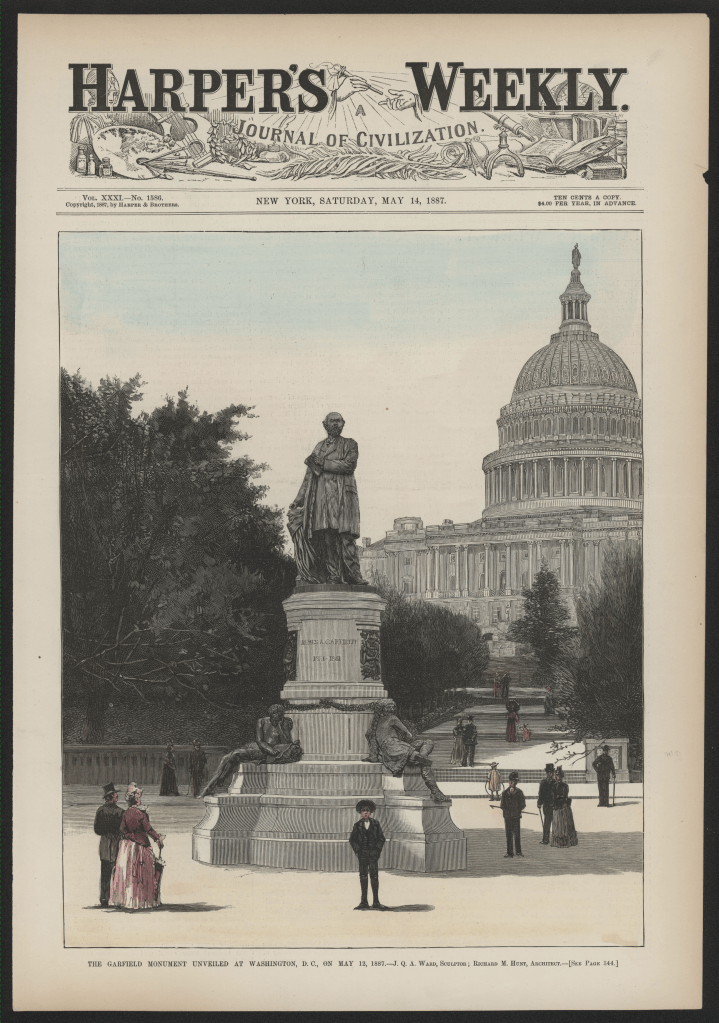

The USS Alliance was a 36-gun frigate of the Continental Navy, commanded at different times by both John Barry and John Paul Jones. She was the last ship of the Continental Navy to be decommissioned.

Throughout the war, Barry devoted his technical skills, wit and personal connections to the fight for independence. When not in command at sea, he joined up with the Continental Army, personally supporting George Washington during the crossing of the Delaware River and at the Battles of Trenton and Princeton.

In the final sea battle of the Revolutionary War, Barry’s ship the USS Alliance was engaged by three British warships. Barry and his crew destroyed one vessel and outmaneuvered the other two.

Aside from his operational duties, he also supervised the construction of warships and authored a manual on ship-to-ship communications.

A 1936 US postage stamp featuring naval heros John Barry and John Paul Jones

After the Revolutionary War ended and the Continental Navy was disbanded, Barry returned to merchant shipping. While not at sea, Barry was well known around Philadelphia for his generosity. He and his wife Sarah raised his two orphaned nephews, cared for other Irish immigrants in town and helped provide for destitute seamen.

Once Washington recalled Barry to active naval service, he began laying the foundation for a permanent United States Navy. He again supervised the construction of new warships (including his own flagship, the USS United States), wrote regulations and mentored the next generation of American naval leaders.

From 1798 to 1801, Barry commanded a naval flotilla in the West Indies, earning him the title Commodore. He is considered the Navy’s first flag officer.

Barry ended his active service in 1801, but would remain in charge of the Navy until his death in Philadelphia in 1803.

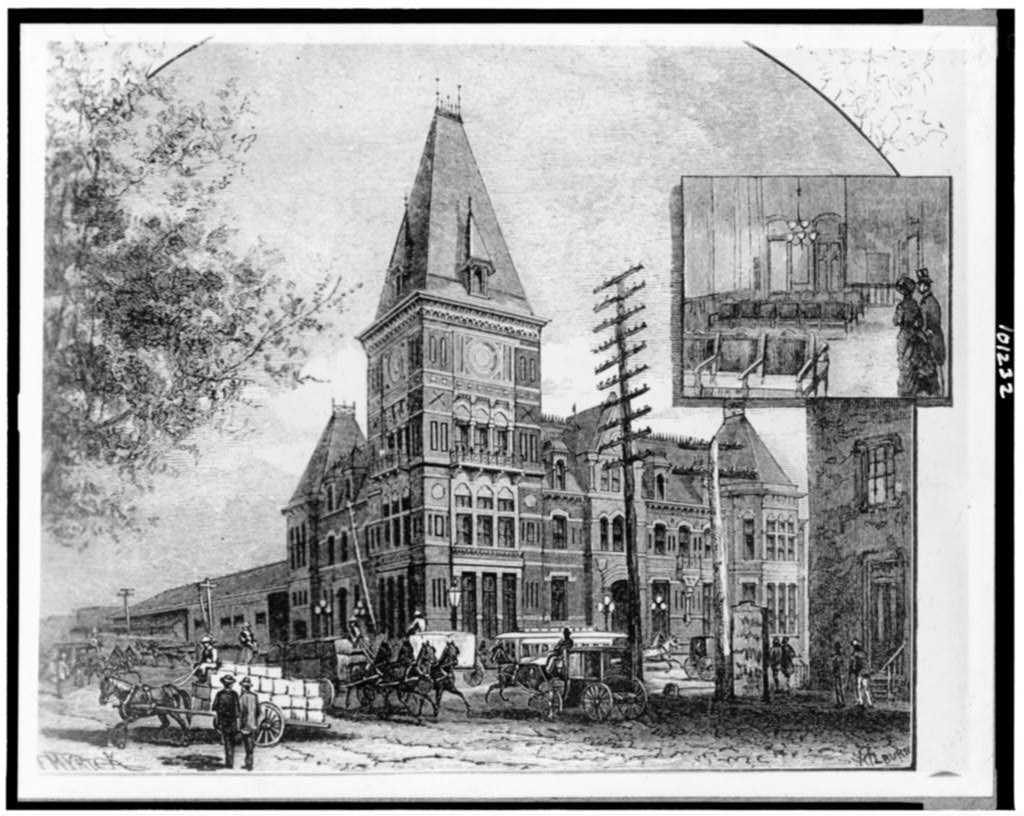

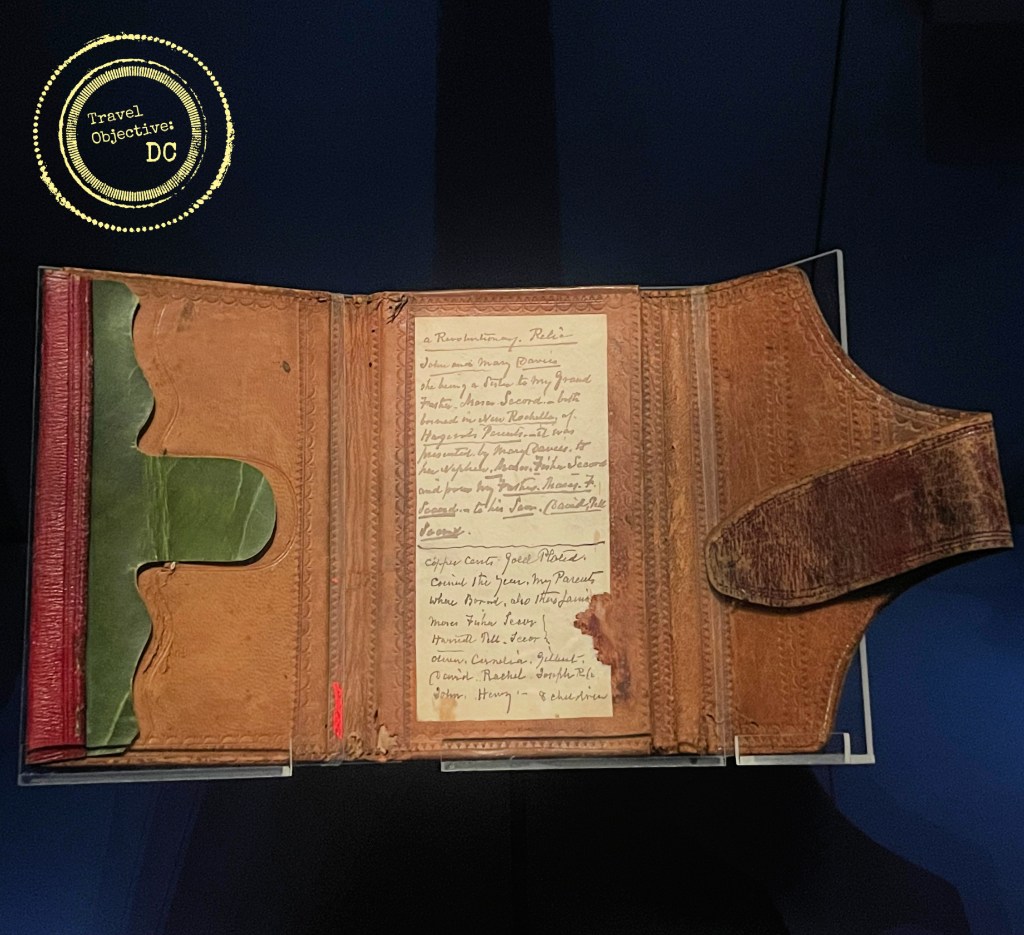

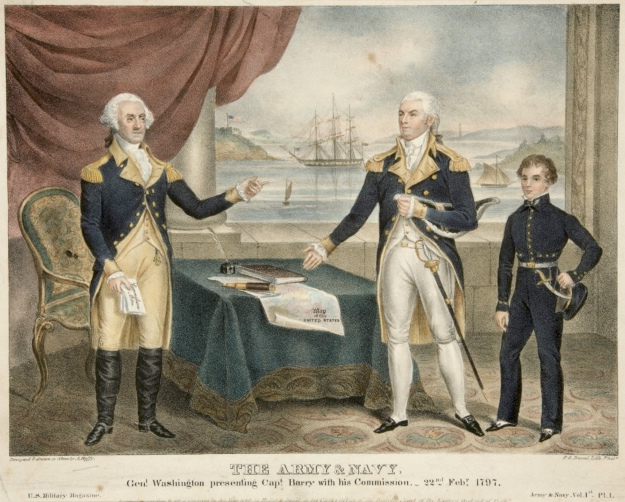

An 1840 lithograph entitled The Army and Navy, Gen’l Washington presenting Capt Barry with his Commission, 22 Feb 1797, by Alfred Holly.

A century later, buoyed by robust Irish immigration to the United States, the Irish community in America sought to recognize one of their own from the War of Independence.

In 1906, Congress approved $50,000 for a Barry statue. Ultimately, a design by sculptor John J. Boyle was selected for the memorial placed in Franklin Park in northwest Washington.

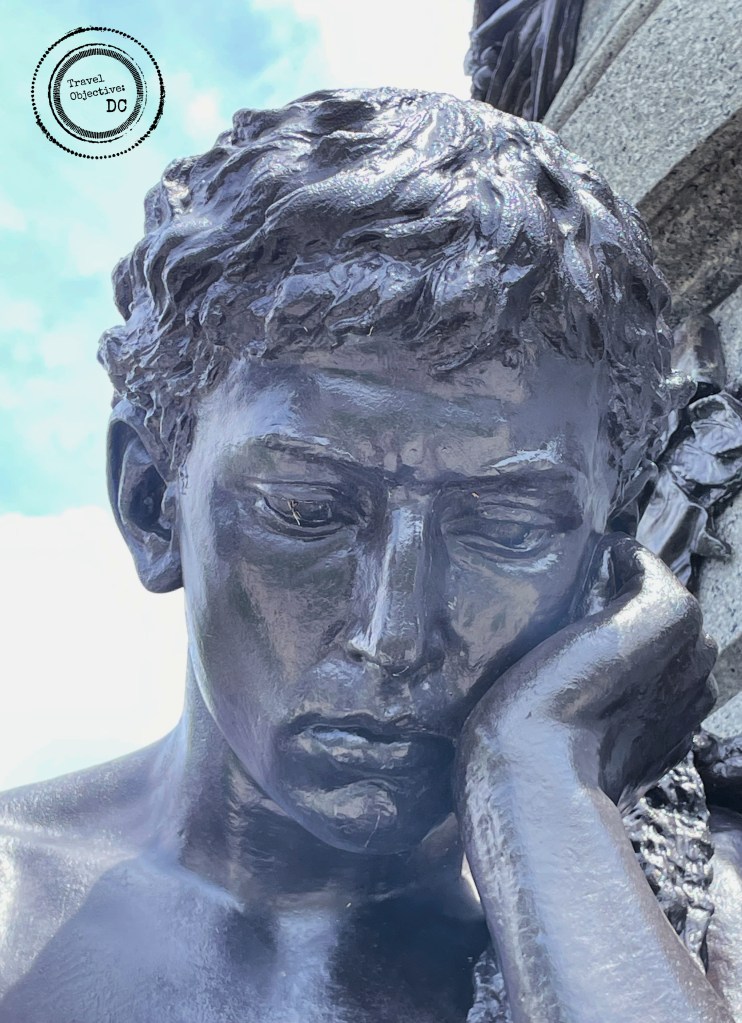

The monument consists of an 8-foot bronze statue of Barry wearing his dress uniform with his right hand resting on his sword. The statue stands on a pink marble base, which in turn rests on steps of pink granite. On the base is a figure of a woman on the bow of a ship. Her raised right hand holds an olive branch with a sword and shield at her left side.

A photograph entitled Unveiling Barry Monument, published by Bain News Service on May 16, 1914

The statue was dedicated by President Woodrow Wilson on May 16, 1914 in a ceremony attended by over 10,000 people. Admiral George Dewey offered remarks and the US Marine Corps Band played patriotic songs.

Through the 20th century, Barry was widely commemorated. There are statues to him in front of Independence Hall in Philadelphia, in his hometown in Ireland, and at the University of Notre Dame. His name is found on academic buildings, plaques, elementary schools and a bridge over the Delaware River. Notably, the U.S. Navy has named four warships for Barry. The most recent is the USS Barry, a guided missile destroyer commissioned in 1992.

His statue in Franklin Park, along with all of these other tributes, fittingly reminds us of the enduring legacy of John Barry — sailor, captain, commodore and proud son of Ireland, who was an even prouder American.

The guided missile destroyer USS Barry (DDG 52)

– Photograph by ST3 Christopher Brewer, US Navy

# # #

Route Recon

The Commodore John Barry Memorial stands along the western edge of Franklin Park in Northwest Washington, DC. Franklin Park is bordered by 13th and 14th Streets on the east and west, and I and K Streets on the south and north. The 5-acre park was renovated in 2021 and now features multiple seating areas, a central fountain plaza and playgrounds.

The closest Washington, DC Metro Station is McPherson Square on the Blue, Orange and Silver lines. The station has an exit at the corner of 14th and I Streets.