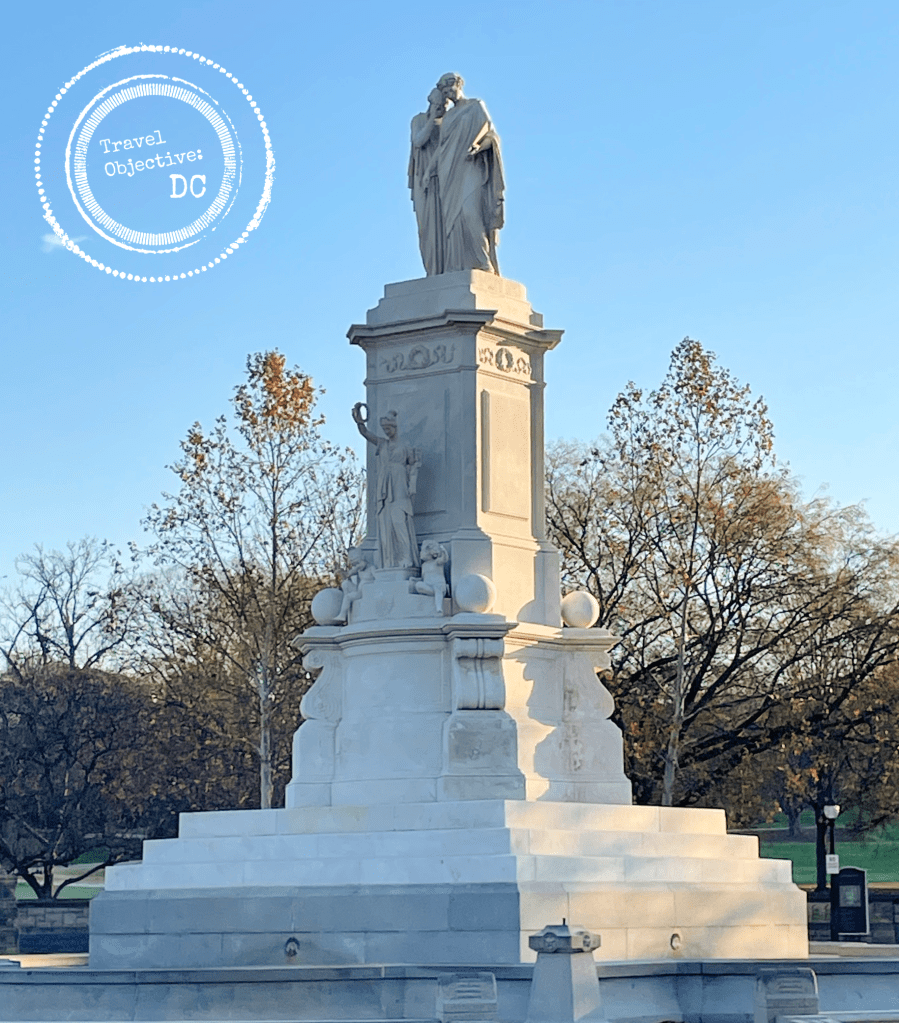

In a large open plaza stands a statue of a solitary figure.

He is a sailor in a dress unform. He stands straight and tall wearing a service “dixie cup” sailor hat. A buttoned up peacoat with a flipped up collar protects him from the chill of the ocean air. His hands are plunged deep into his pockets. His packed sea bag stands by his side. The determined look on his face denotes his readiness to deploy anywhere and perform his duty.

The statue is known as The Lone Sailor and serves as the centerpiece of the US Navy Memorial.

The Lone Sailor Statue

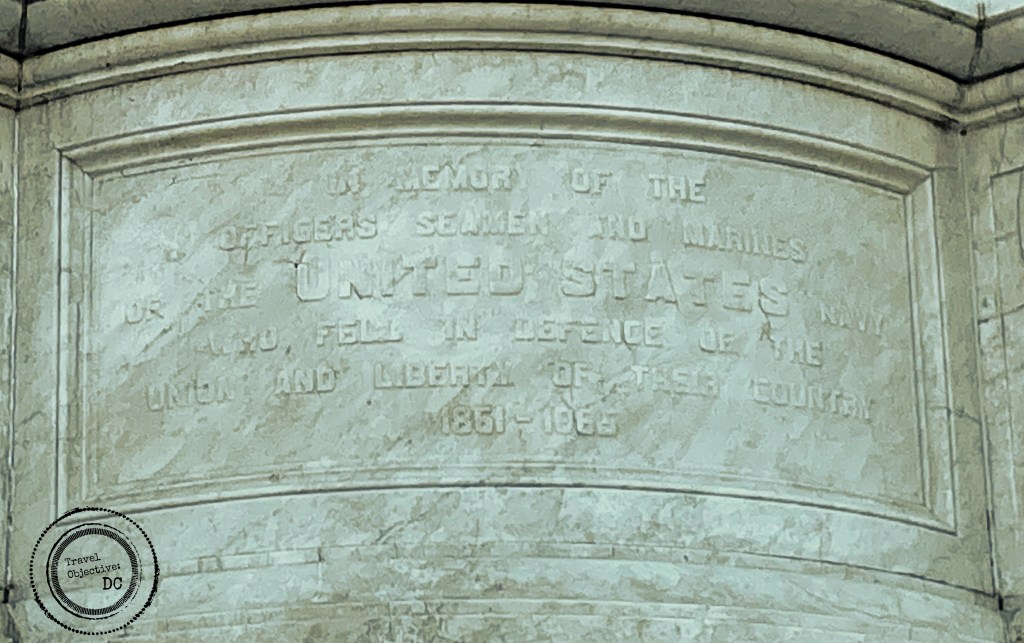

For centuries, considerable discussion was had regarding a suitable monument paying tribute to the United States Navy. Pierre L’Enfant had included a Memorial Column for the Navy in his original plans for Washington, DC. Other memorials were built to honor the Navy during specific conflicts, but nothing existed to honor all American sailors.

This all began to change in the spring of 1977 as Admiral Arleigh Burke urged Navy senior leaders and veterans to get serious by proclaiming: “We have talked long enough about a Navy Memorial, and it’s time we did something about it.”

When Admiral Burke–a distinguished World War II war hero and three-time Chief of Naval Operations–spoke, Navy personnel listened. The Navy Memorial Foundation was quickly organized and Rear Admiral William Thompson was named its first president. Admiral Thompson proved an excellent choice for the job and quickly set to work.

Rear Admiral William Thompson (ret.), on left, receiving a donation for the US Navy Memorial. Note the artist’s rendition of the Memorial.

-Department of Defense Photo

He first helped shape the enabling legislation Congress would pass in 1980. He then led the foundation through selecting the memorial’s designers, determining the memorial’s location, raising money and overseeing construction.

Admiral Thompson also helped select the sculptor Stanley Bleifeld to design and sculpt The Lone Sailor Statue. In recognition of Admiral Thompson’s significant contributions to building the memorial, Bleifield included Thompson’s initials on the Lone Sailor’s sea bag.

The Navy Memorial Plaza looking south toward the National Archives

The whole process from the founding of the memorial to its completion stretched to almost a decade. The Navy Memorial was formally dedicated on October 13, 1987 by President Ronald Reagan. He devoted it to all who have served, are serving or will serve in the United States Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard and Merchant Marine.

The memorial is set within a broad circular plaza to the northwest of the intersection between 7th Street and Pennsylvania Avenue. Early designs for the memorial favored a more traditional approach, but they were discarded in favor of a memorial with a more open space resembling a seascape.

The floor or base of the plaza depicts a large world map. With a diameter of 100 feet, it is said to be the largest map in the world.

A set of fountains at the US Navy Memorial

Fountains skirt the southern perimeter of the map. The water flowing through the fountains comes not from Washington DC’s water supply but is collected from the world’s oceans and the Great Lakes.

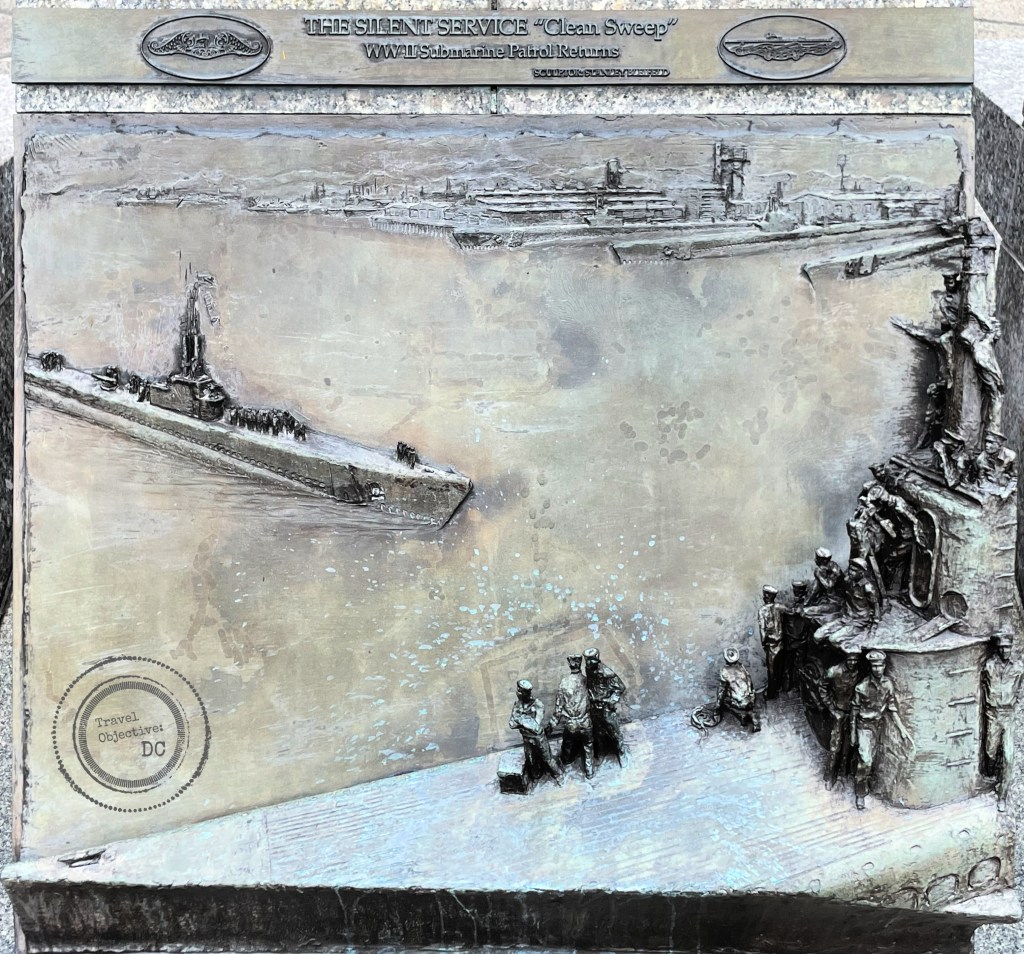

A semicircular wall inside the fountains contains a series of 26 bas-relief figures depicting scenes of Navy history and Navy life as well as the contributions of maritime partners.

Arrayed around the memorial are quotes about the Navy from sailors at all levels. Six masts fly the flags of the United States, the Navy, Marine Corps, Coast Guard, Merchant Marine and the POW/MIA flag.

Bas Relief sculpture of Navy submarines in World War II

Sweeping arches incorporated into the design of two mixed-use commerical buildings suggest a northern perimiter to the memorial, balancing the fountains and sculpture walls on the southern side. The neoclassical design of these buildings seemingly provides a sense of the shore or anchorage to the airy, open plaza.

Amidst all this stands The Lone Sailor. The statue has been so enthusiastically received by the Navy community, there are 18 more Lone Sailor statues across the United States (and one at Utah Beach in Normandy). In each location, the statue reminds the community of the dedication and professionalism of the American sailor.

Bas Relief Sculpture of Captain John Paul Jones

Early in the design phase, the Navy identified a desire to have a “living memorial,” a place where people would gather and return to time and again. The open space makes the memorial a popular venue for summer concerts, reenlistments, promotion ceremonies, wreath layings and reunions.

In keeping with the desire for a living memorial, the Navy Memorial Foundation located a visitor center in one of the adjoining buildings. Part research facility, part musuem and part community center, the visitor center brings the Navy experience alive for the landlubber while instilling pride in all Navy sailors. There are exhibits on the missions of the post 9/11 Navy, multiple Navy leaders, and the important role played by chief petty officers.

The visitor center also houses the Arleigh Burke Theater. In addition to running several short movies on Navy life throughout the day, as well as periodic feature films, the theater hosts guest speaker programs. Visitors can find a variety of mementos from all the US military services at the Ship’s Store gift shop.

A video screen displays the Navy Log throughout the day.

There is also a feature known as the Navy Log, an online archive with details of the men and women who have served in all the sea services. There are currently over 750,000 entries. Active members, veterans or their loved ones are invited to add to this number and enter a service member’s information as an ongong tribute to their time in uniform.

As the US Navy observes its 250th Anniversary, the US Navy Memorial is a place for everyone to discover and honor America’s rich naval heritage. Whether you are active, retired, reserve or the relative or friend of someone who has served, the Navy Memorial is an important and worthwhile destination for any visit to Washington, DC.

***

I can imagine no more rewarding a career. And any man who may be asked in this century what he did to make his life worthwhile, I think can respond with a good deal of pride and satisfaction: ‘I served in the United States Navy.’

President John F. Kennedy

Route Recon

The US Navy Memorial is located at 701 Pennsylvania Ave, NW Washington, DC 20004.

The Memorial is accessible 24 hours a day.

The Visitor Center is open seven days a week from 9:30 AM to 5:00 PM.

The Navy Memorial hosts numerous events throughout the year. Some events may close the Visitor Center to the public. Be sure to check the Memorial’s website and find additional information about upconing events on the calendar.

The closest Metro Station is Archives-Navy Memorial-Penn Quarter on the Green and Yellow Lines.

Parking:

Validated parking is available at PMI Garage, 875 D Street, NW.

Parking can be validated for $13 inside the Ship’s Store, located in the Navy Memorial Visitor Center.