As the smoke cleared at Lexington and Concord on that fateful April day in 1775, supporters of American independence relished in the successes of the brave militia forces.

But they well understood the cause for independence would take a well-trained regular army capable of defeating the British on an open battlefield. Furthermore, this army needed to represent all of America and not dominated by a single colony or region.

On June 14, 1775, the Continental Congress established the Continental Army and appointed George Washington as its commander in chief. In recognition of the Army’s 250th Anniversary, the National Museum of the US Army, at Fort Belvoir, Virginia has opened a special exhibit entitled Call to Arms: The Soldier and the Revolutionary War.

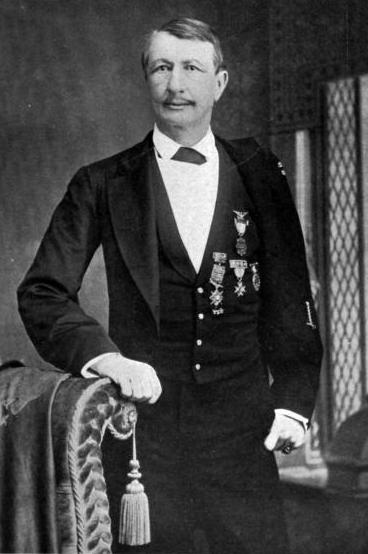

This pair of major general epilettes belonged to Jeddidiah Huntington of Connecticut. Huntington had encouraged George Washington to adopt this design for general officers’ epilettes.

To tell their stories, museum curators sought and received an abundance of unique and important Revolutionary War era pieces from state governments, private collectors and international organizations. The resulting assemblage of weapons, uniforms, colors and everyday articles includes items that have not before been on public display in the United States.

The 5,000 square foot exhibit is laid out in roughly chronological order. Two innovative topographical battle maps–one of Bunker Hill, the other of Yorktown–bookend the exhibit representing the first and the final battles for the Continental Army. Similar to the twinkle light maps of the past, these three dimensional representations depict the operational plans and troop movements of each battle, accompanied by slick videos providing additional context.

Other battles and campaigns are briefly described with corresponding artifacts, maps and illustrations to connect the visitor to the period. The early struggles in New York and Pennsylvania, the successes in New Jersey, the turning point at Saratoga and the Southern Campaign are put in context and placed in a timeline. Videos enhance these displays describing aspects of 18th century warfare, such as weapons and battlefield tactics.

These displays with brief summaries are a reminder that these battles were fought by soldiers from across the new country. In an era when few people traveled very far from their homes, New Englanders fought in South Carolina and Virginians fought in Pennsylvania. The seeds of our national identity were planted on the battlefields of the Revolutionary War.

A British 3-Pounder gun tube captured at the Battle of Saratoga

Those interested in 18th century weaponry will not be disappointed in their visit. There are many splendid muskets, rifles, carbines, pistols, swords and bayonets. However, the real focus of Call to Arms is the lives of Continental Army soldiers, their motivations, successes, experiences and how they emerged as an effective fighting force.

The lot of a soldier in the Continental Army was a difficult one. Living conditions were challenging, pay was inconsistent, rations and supplies were usually in short supply. These rigors of military life were shared by soldiers from every state.

Still, Americans from the north and south, coastal cities and frontier homesteads answered the call. Then, as now, soldiers enlisted for different reasons. They fought for independence, but also for their communities, comradery, pay, a sense of adventure or because other family members or friends also enlisted.

A plaster casting of Anna Maria Lane, wife of Private John Lane. She followed her husband to camp when he enlisted in the Continental Army in 1776. She took up arms herself and was wounded at the Battle of Germantown in 1777.

Over the eight years of Revolutionary War, about 231,000 men (and some women) served in the Continental Army. Enlistments would ebb and flow based on any number of factors, such as the time of year, local economic conditions and success of the army in the field. The maximum size of the army at any one time was about 48,000 troops.

A portion of the exhibit entitled Camp Life explores the life of the Continental Army soldier away from the battlefield. What soldiers ate, where they lived and their daily activities, such as drill, guard duty and the building of fortifications, are all examined.

A notebook belonging to British Major John Andre. His capture in 1780 led to the identification of General Benedict Arnold as a traitor.

One of the more intriguing group of artifacts are a display of powder horns. These hollowed-out animal horns were essential kit for 18th century soldiers, allowing them to quickly add gunpowder to the flashpans of their flintlock muskets. Soldiers often decorated their powder horns or used them to record important dates or locations.

Accompanying the display is a video screen where digitized images of the complete powder horns can be viewed by visitors to more clearly see the intricate designs. Information about the original owner is also available. The richly decorated powder horns remind us these early soldiers were more than faded names on yellowed muster rolls, but real people fighting for something they believed in.

A powder horn belonging to Private John Bond of Massachusetts. Bond enlisted in the Continental Army on July 4, 1775 and served for five years. He fought at the Battle of Bennington in 1777.

Also included in the exhibit are several very detailed cast figures representing specific individuals who served with the Continental Army. There is southern aristocrat, a Native American tribal chief, even a married couple who served together. They add an important human element to the exhibit’s interesting array of artifacts, well-designed graphics and use of technology.

Continental Army soldiers met many struggles during their service. Sadly, they encountered more upon returning home.

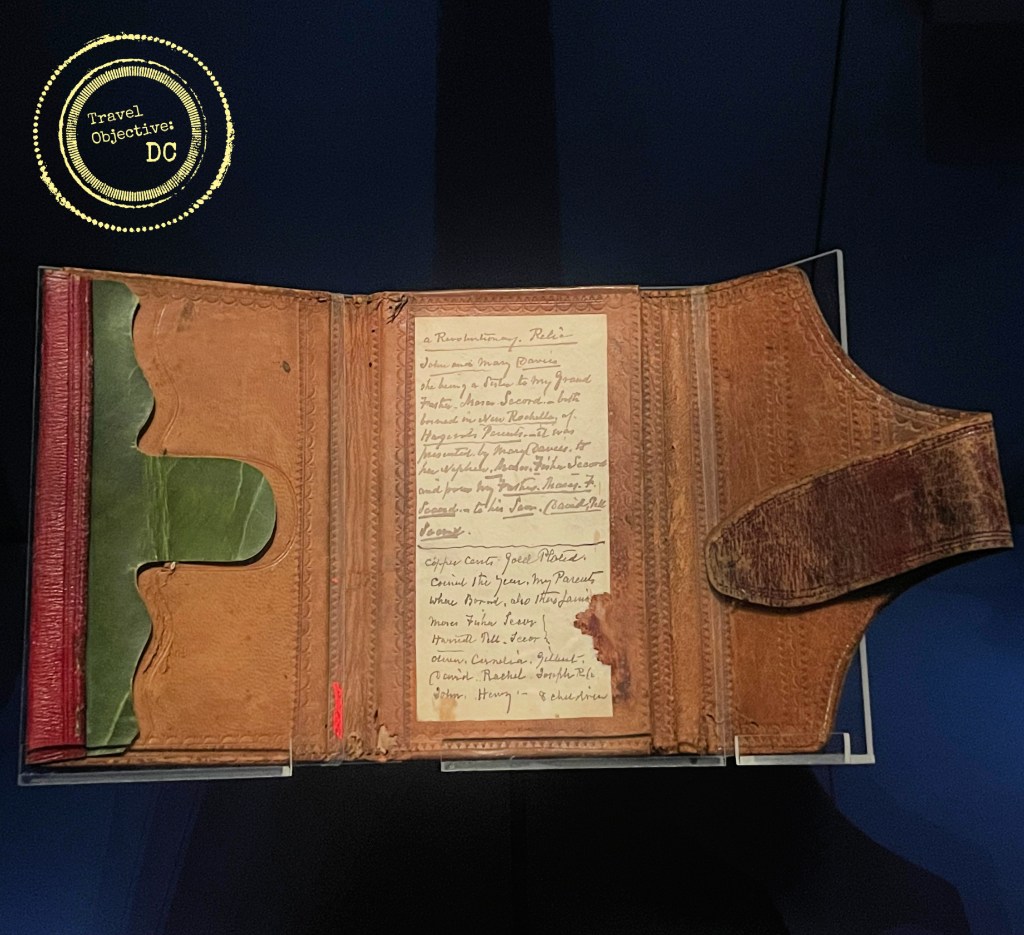

At the end of the exhibit is a collection of documentation which mark the beginning of the process well known to today’s veterans and their families, applying for benefits. At the end of the war, many soldiers went home with promissory notes in lieu of their pay and they struggled economically. Legislation to provide pensions to veterans was slow in coming.

Congress did not pass legislation providing pensions to common soldiers until 1818, thirty-five years after the end of the Revolutionary War. By this time, many veterans had died or lost important records that proved their service. This display though shows pension applications and examples of the documents that Continental Army veterans or their survivors would provide, such as muster roles, discharge papers, and pay records.

The discharge document of Drummer Benjamin Loring of the 2nd New York Artillery.

Call to Arms artfully tells the story of the Continental Army, with its wonderful artifacts and state of the art technology. It reminds us of an important lesson first demonstrated by the Continental Army and continued in today’s United States Army.

George Washington reflected on it in his farewell message to his troops as he wrote: Who that was not a witness would imagine … that Men who came from different parts of the Continent … would become but one patriotic band of Brothers.

Washington well understood the unity forged among his soldiers was crucial for achieving their shared goal of victory.

250 years later, it is still a lesson to remember.

* * *

Route Recon

Call to Arms is on display at the National Musuem of the United States Army until June 2027. The musuem is open daily from 9:00 AM – 5:00 PM except on Christmas Day. Visit the museum’s website for free entry tickets.

The musuem is located in a publically accessible portion of Fort Belvoir, Virginia. The museum address is 1775 Liberty Drive, Fort Belvoir, VA 22060, but be aware not all GPS systems recognize the Museum’s street address.

You can download a map with directions here.