Today, few Americans could tell you very much about James Abram Garfield, our 20th President. A few people with an interest in history might recall that Garfield was assassinated early in his presidency by a “disgrunted office seeker”. Professional historians generally rank his shortened presidency as “below average” or do not rank him at all.

This is rather regrettable as Garfield was a courageous and dedicated leader who died for fighting what he believed in. Fortunately, he has one distinction the vast majority of presidents will never have: his own memorial on the US Capitol grounds.

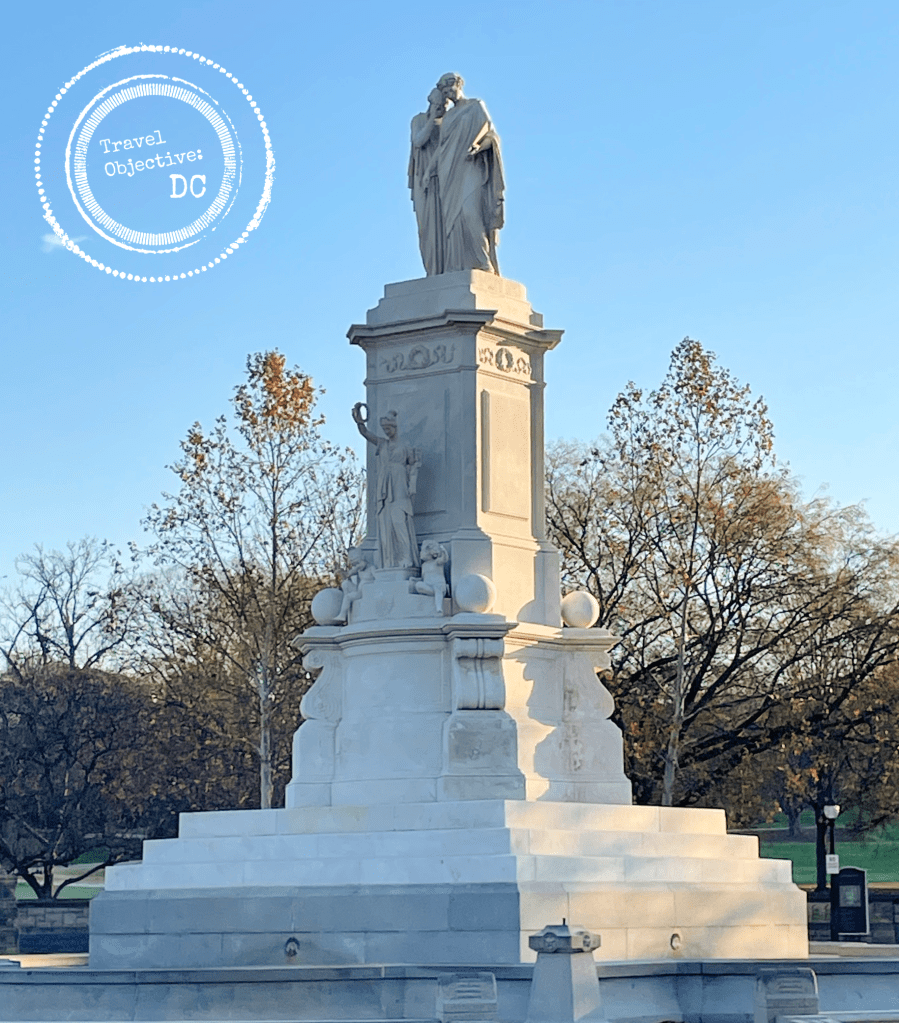

One of three monuments on the west side of the Capitol building adjoining the National Mall–along with the Ulysses S. Grant Memorial and the Peace Monument–Garfield’s monument is located within a traffic circle at the intersection of First Street SW and Maryland Avenue near the US Botanic Garden.

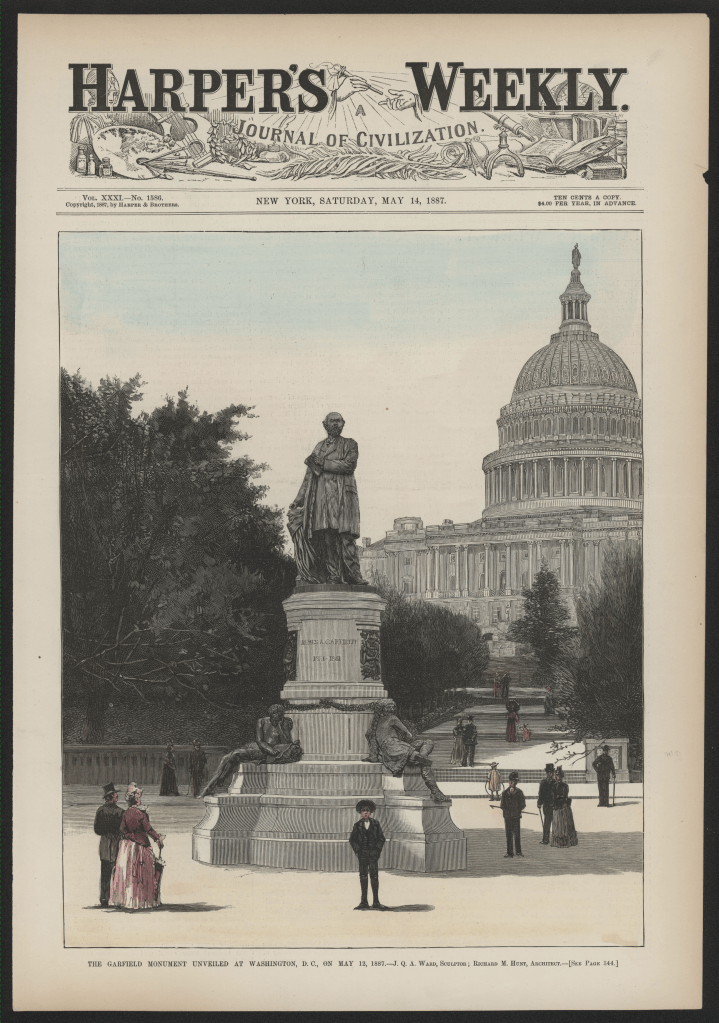

The Garfield Memorial on the west grounds of the US Capitol

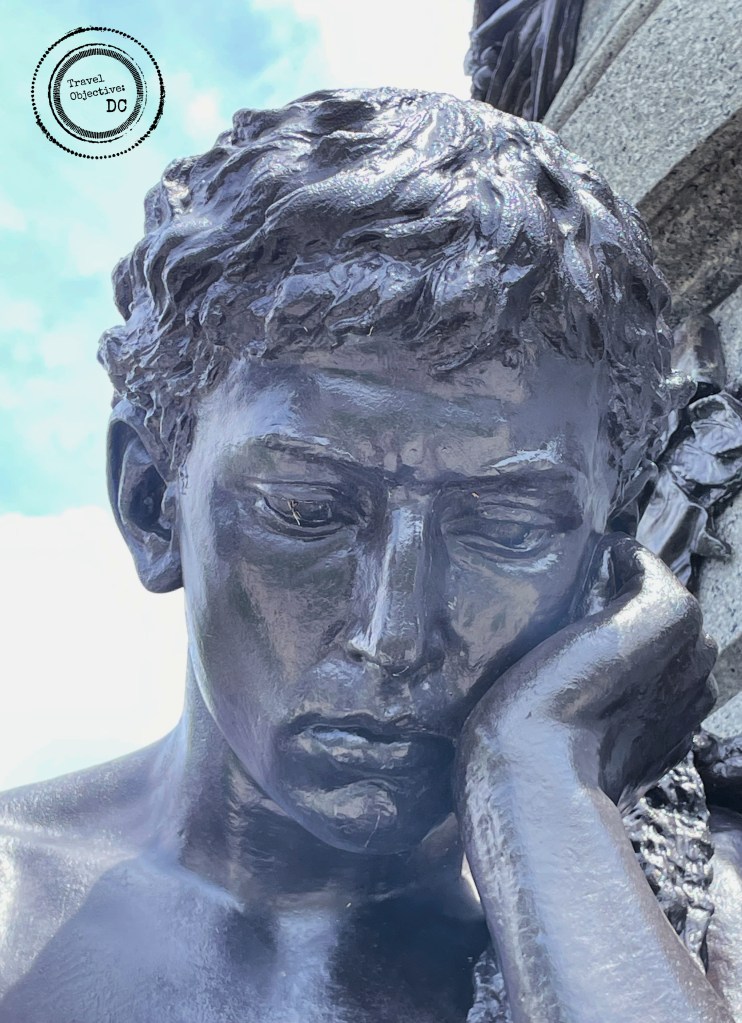

John Quincy Adams Ward, a prominent 19th century sculptor and friend of Garfield designed the monument. Ward depicted Garfield in bronze atop a round, tapered granite pedestal. He is shown giving a speech, grasping a scroll in his left hand and gazing intently at his audience. His foot is placed slightly off the platform and meant to symbolize Garfield as a man of action. At the base of the pedestal are three classical Roman figures representing the key phases of Garfield’s life as a young scholar, military leader and statesman.

Garfield personified the American success story, so much so that renowned author Horatio Alger wrote his biography. Alger published From Canal Boy to President in 1881.

James Garfield was born in 1831 in a log cabin in northeastern Ohio. His family was poor and his father died when Garfield was a young man. He went to work to support his family, taking a variety of jobs including helping tow canal boats. While recovering from a serious bout of malaria contracted on the canal, Garfield’s mother convinced him to return to school. Garfield was an excellent student with a strong work ethic. He took to his studies and worked his way through the Western Reserve Eclectic Institute as a janitor and school teacher. After graduation, he became a preacher. Garfield then studied law at Williams College in Williamstown, MA.

The face of the young scholar figure on the Garfield Monument

Between his jobs as a preacher, teacher and lawyer, Garfield became a skilled orator. He entered politics and was elected to the Ohio State Senate as a Republican in 1860. As the Civil War broke out, Garfield was an abolitionist dedicated to the Union’s cause. He led fundraising and recruitment efforts for Ohio volunteer regiments.

Eager to enter the Army, Garfield began studying military tactics.

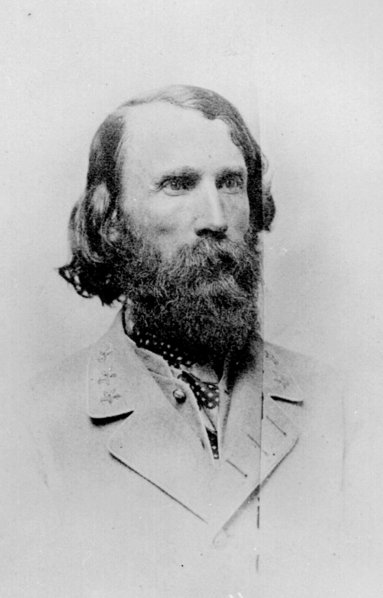

Garfield commanded a Union Army brigade at the Battle of Middle Creek near Prestonsburg, KY in January 1862. Under his steady leadership, Garfield’s troops routed the rebel forces who retreated into Virginia. Although not considered a major battle today, the victory was an important boost to Union morale and brought Garfield widespread recognition.

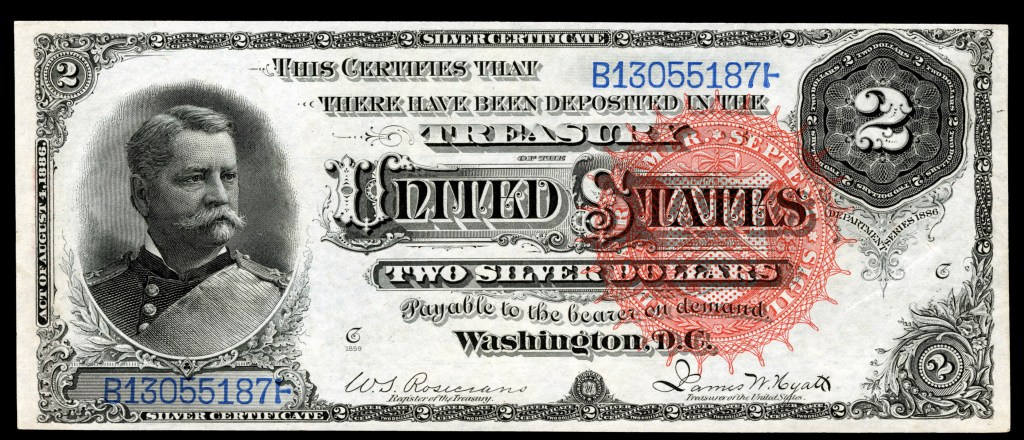

After the battle, Garfield was promoted to brigadier general. He was later assigned as Chief of Staff to General William Rosencrans of the Army of the Cumberland. After the decisive Union loss at the Battle of Chickamauga, Ulysses S. Grant relieved Rosencrans of command. Rather than Garfield, Grant appointed George H. Thomas to succeed Rosencrans. Although Garfield was later promoted to Major General, being passed over for the army command led him to consider a return to politics.

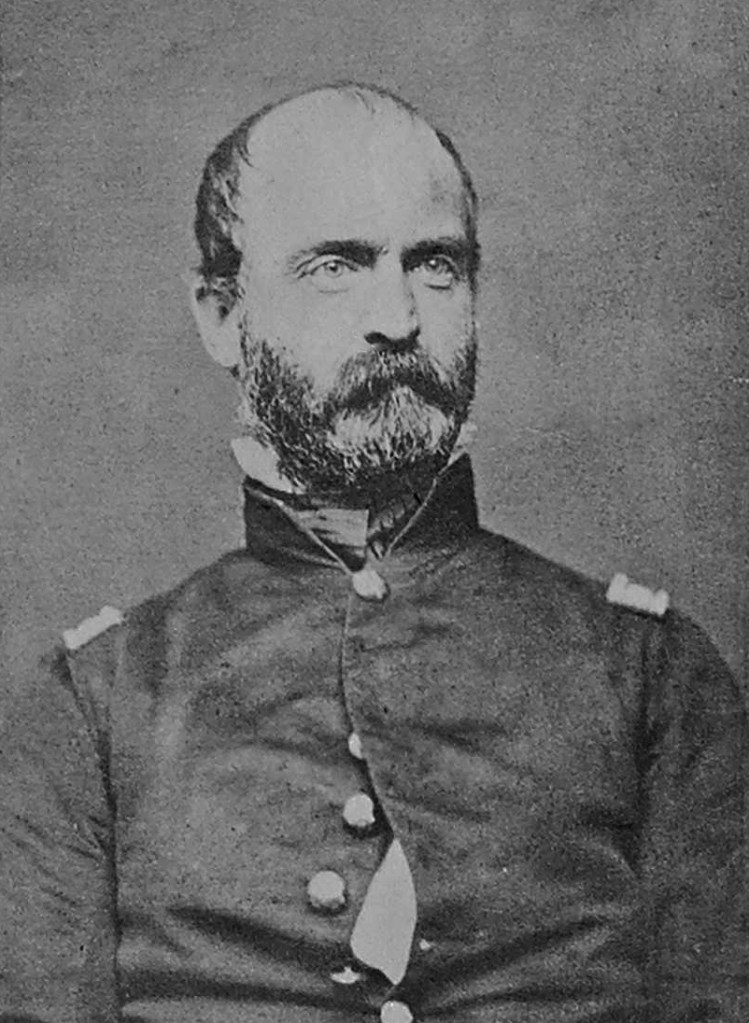

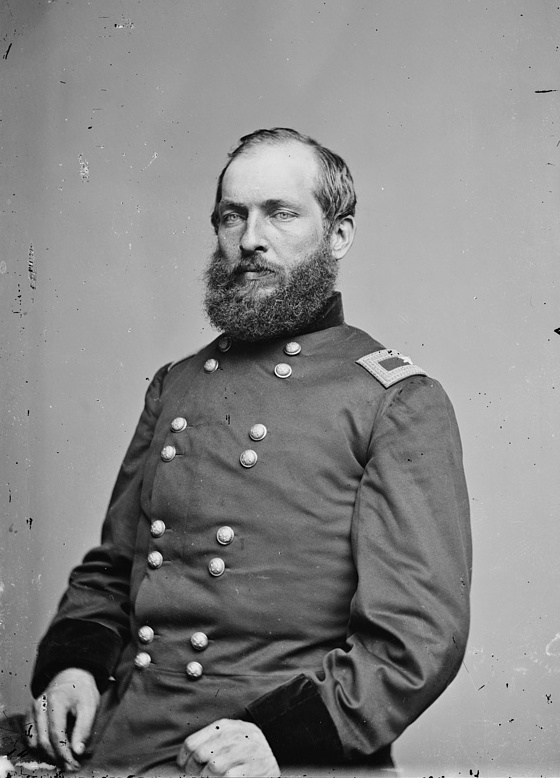

Brigadier General James Garfield, circa 1862

-Retrieved from the Library of Congress

In 1862, Garfield won an election for a seat in the House of Representatives. Garfield would serve nine terms in the House representing his home state of Ohio. While in Congress, Garfield was known for supporting civil rights for African Americans, the gold standard for the US dollar, and improving education for all. He helped establish the Federal Bureau of Education in 1870 to study and enhance educational methods across the country.

Garfield excelled as a Congressman, chairing powerful committees and mastering the nuanced details of legislation, especially on financial matters. At the same time, he was affable, a good conversationalist and considered one of the nicest men in Washington.

At the deadlocked Republican presidential convention in 1880, Garfield was nominated on the 36th ballot. He defeated his fellow veteran Winfield Scott Hancock in the general election and was sworn in as the 20th President of the United States on March 4, 1881. (He is the only president to be elected while a serving member of the House).

During his presidency, Garfield fought one very significant battle.

His victory in that battle still impacts us today.

It had long been the practice in America that Federal employees were selected based on their demonstrated loyalty to political parties. Senators and representatives from a newly elected president’s party would act as “patrons” and recommend party workers, relatives and financial backers to the administration for government jobs.

In the 1870’s, the issue of patronage was splitting the Republican party. Many wanted to maintain patronage while others wanted reform. Garfield opposed the patronage system and was a proponent of a professional, apolitical civil service. He knew it would make the Federal government much more efficient, limit corruption, and relieve elected officials from constant demands for jobs.

Garfield staged a showdown with New York’s two powerful Republican senators who were both savvy practitioners of the patronage system. Garfield nominated his own candidate for the important position of customs collector in the Port of New York. The two New York senators resigned in protest fully expecting to be quickly returned to office by the New York legislature. However, during their absence from Washington, Garfield pushed his nomination through the US Senate, embarrassing the two senators.

Sadly, this important victory over patronage directly contributed to Garfield’s death.

On July 2, 1881, Garfield was preparing to board a train at Washington’s Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station. Suddenly, two shots rang out, striking Garfield in the arm and back. Garfield’s assailant was Charles Guiteau, who may forever be known in history books as the “disgruntled office seeker”.

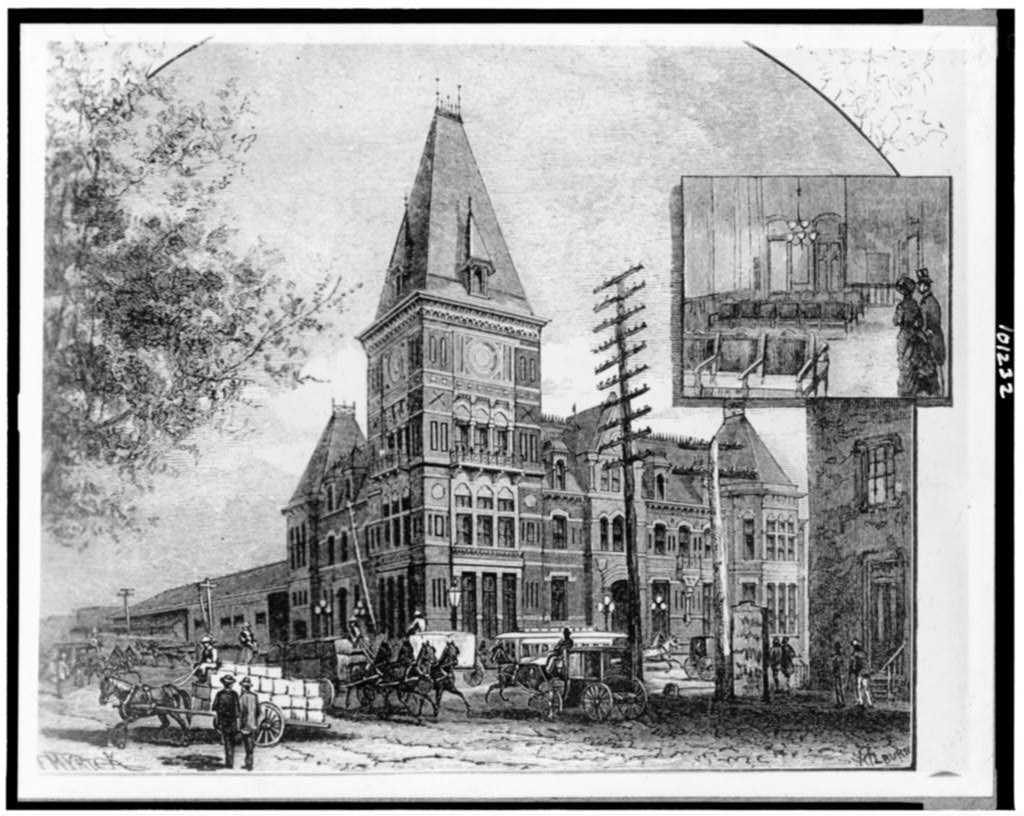

The old Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Station. The station was demolished in 1907 after Union Station was opened. The station was located where the West Building of the National Gallery of Art stands today. [Undated photo]

-Retrieved from the Library of Congress

Guiteau had written, delivered and published a speech supporting Garfield in the election. He thought this entitled him to a consular job at the US Embassy in Paris. While Guiteau had no dislike for Garfield as a person, he believed he would help preserve the patronage system by killing the president. Guiteau was quickly apprehended in the train station. He was later found guilty of murder and executed about 18 months after the shooting.

The cover of Puck, a 19th century satirical magazine from July 13, 1881 with an image of Garfield’s assassin Charles Guiteau holding an extortion note.

Garfield would linger on for the next two months. On September 19, 1881, he died from sepsis poisoning, just five and an half months into his presidency.

In the wake of Garfield’s death, Congress passed the Pendleton Act, which established a merit-based system for hiring and promoting Federal employees. The Pendleton Act was signed into law by the new president, Chester A. Arthur, who previously had been a supporter of the patronage system. As a surprise to many, Arthur quickly set about implementing its provisions to reform the civil service.

The country closely followed Garfield’s deterioration and he was widely mourned after his death. Work then quickly began on building him a suitable memorial. The Society of the Army of the Cumberland, a Union veterans’ organization, formed a fundraising committee and ultimately raised over $28,000. They also successfully lobbied Congress for additional funds for the statue and the pedestal.

The newly unveiled Garfield Memorial was prominently placed on the cover of Harper’s Weekly on May 14, 1887.

The memorial was dedicated on May 12, 1887, in a grand ceremony attended by President Grover Cleveland, many senior government officials, military leaders and veterans from the Society of the Army of the Cumberland and the Grand Army of the Republic. Cannon salutes were fired and the US Marine Corps Band played stirring patriotic music.

Today, the Garfield Memorial remains a prominent and visible reminder of the talented, resourceful and considerate man who was our 20th president.

* * *

Route Recon

The Garfield Memorial is located within a traffic circle at the intersection of First Street SW and Maryland Avenue near the US Botanic Garden.

There is limited street parking nearby near the Botanic Garden.

The closest Metro Station is at L’Enfant Plaza. Exit the station through Entrance A for 7th Street and Maryland Avenue. Follow Maryland Avenue to the northwest, pass the Dwight D. Eisenhower Memorial and the US Botanic Garden.