Lieutenant Arthur Raymond Brooks, US Army Air Service, knew he was in for a fight.

In the skies above Mars-la-Tour, France on September 14, 1918, Brooks and his squadron of six SPAD XIII fighters encountered four squadrons of German Fokker D.VIIs. As the fighter planes engaged each other, Brooks flew directly into German machine gun fire. He then quickly pulled away from his main formation with eight German fighters in pursuit.

Brooks next used all the maneuver capabilities the SPAD could provide to avoid being caught in a Fokker’s line of fire. He did barrel rolls. He flew in loops. He quickly climbed, then rapidly dove.

As the melee continued, Brooks fired on multiple Fokkers as they all weaved through the sky, downing two. German fire shattered his windshield and damaged one of his two machine guns. His SPAD was riddled with bullet holes. Yet he stayed in the fight. Brooks anecdotally shot down four German fighters that day (although he was only credited with two) and was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his actions.

The SPAD XIII Fighter – Built by the Société Pour L’Aviation et ses Dérivés (SPAD) company, the SPAD XIII was preferred by French aces. The US Army Air Service also flew SPADs. Ray Brooks flew this SPAD in October 1918.

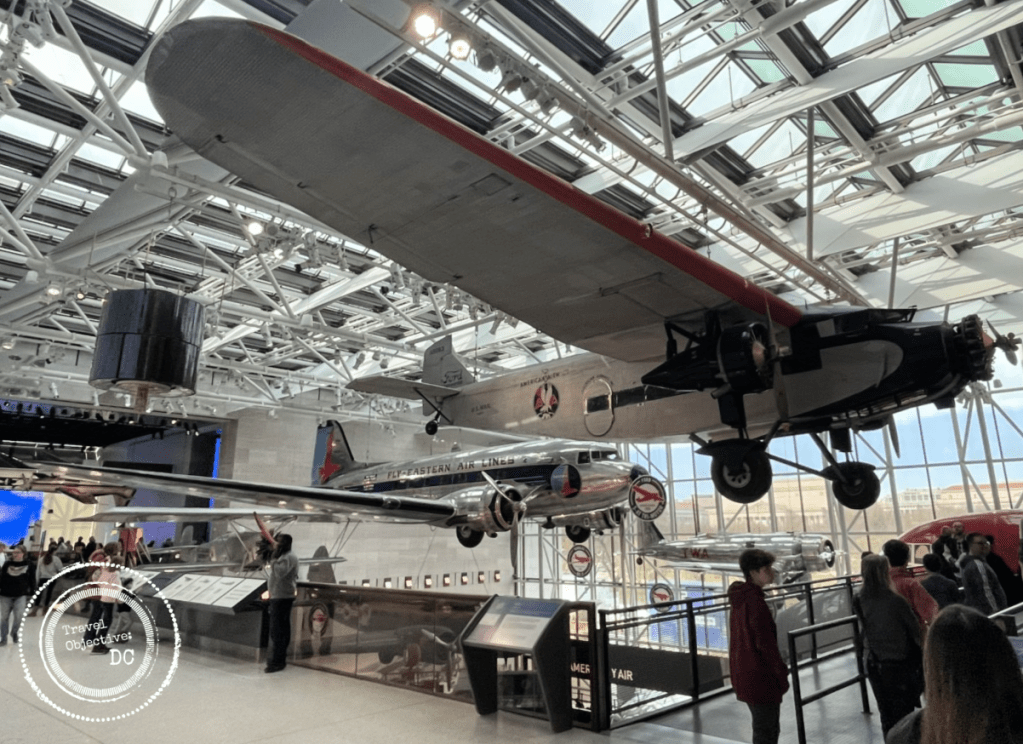

Ray Brooks is just one pilot whose aerial exploits are recounted in the Smithsonian Institute’s National Air and Space Museum’s (NASM’s) redesigned World War I aviation exhibit entitled World War I, the Birth of Military Aviation.

This is NASM’s third exhibit dedicated to the aircraft and aerial warfare of the First World War. The earlier exhibit, entitled Legend, Memory and the Great War in the Air, closed in 2018 as NASM prepared for a musuem-wide refurbishment. The new iteration explores the twin themes of how “the Great War” defined the on-going nature of military aviation as well as the remarkable experiences of World War I aviators.

There is much to see in the new gallery, but the meticulously restored World War I aircraft are the main attraction. Many of the World War I airplanes previously displayed are back. Greeting you from overhead as you enter the exhibit hall are the French Voisin Type 8 nighttime bomber and the German Albatross D.VA, a fighter that debuted in 1917. Other aircraft include the Fokker D.VII German fighter, Ray Brooks’ SPAD XIII fighter and the DH-4 Liberty Plane.

A German Albatross D.Va Fighter – These fighters were introducted in 1917.

The latest exhibit occupies a smaller footprint than its predecessor, but NASM’s designers have filled the space with a wide range of intriguing artifacts, vintage aircraft, airplane models and other displays.

The exhibit timeline from 1914 through the post-war period is arranged in a counterclockwise manner around a beautifully restored Sopwith F.1 Camel (the last surviving Camel fighter produced by the Sopwith Aviation Company). Once a pilot mastered the British-made aircraft’s finicky controls, the Camel was a highly versatile fighter. It is credited with downing more enemy aircraft than any other Allied plane.

Unlike other aircraft on display, the Sopwith Camel is placed on the floor making it the easiest to see and admire.

Adjoining the Camel is a large movie screen surrounded by a tent-like frame, suggesting an early aerial hanger. A four-part narrated film plays on a loop showing period aircraft in flight. The film provides a wonderful sense of motion to these beautiful but otherwise static aircraft.

The Sopwith F.1 Camel – This aircraft is the last surviving F.1 Camel built by the UK’s Sopwith Aviation Company.

Through the war years, three distinct types of military aircraft evolved–reconnaissance planes, fighters and bombers–reflecting the three original mission areas of military aviation.

To battlefield commanders, the airplanes’ most critical function was reconnaissance and observation. Trench warfare had ended the traditional scouting role of horse cavalry, but aircraft could find, fix and observe the enemy from above. Reconnaissance aircraft were built to direct artillery fire, track troop deployment, assess damage and relay messages over long distances. Planes were fitted with cameras and communications equipment, essentially becoming the commanders’ eyes and ears. Pilots and observers risked their lives to take photographs, which were now an important element of military planning.

A Kodak A-2 Oblique Aerial Camera. A 4″x5″ glass plate was changed out each time a picture was taken.

Fighter aircraft were first developed to protect the reconnaissance planes. Ultimately, the fighters would engage each other to control the airspace over the trenches. Later in the war, Britain and Germany formed special fighter squadrons to directly attack troops on the ground.

Airships also conducted reconnaissance as well as bombing missions. However, their large size and slow speed made them susceptible to attack by fighters. They were generally replaced on bombing missions with specialized aircraft capable of flying further and higher while carrying heavier bomb loads.

Cross insignia from a German airship – This design was the official emblem of the German Air Service until mid-1918.

World War I gave rise to the military aviator as a distinct specialty. Some aviators, especially pursuit (later called fighter) pilots, took on a mythic status in their home countries. Flying high above the mud and blood of the trenches, these pilots were heirs to the chivalrous legacy of knights in armor. Pilots were written about in newspapers, appeared on magazine covers and made public appearances.

Prominent pilots included in the exhibit include Eddie Rickenbacker (America’s most decorated WWI ace), Manfred von Richtofen (The Red Barron), Eugene Bullard (African-American pilot flying for the French), Raol Lufbrey (a French-American ace), and Snoopy. (OK, Snoopy was not a real pilot, but he does have his own display, which is, of course, by the Sopwith Camel).

Among all the aircraft and artifacts, there are many interactive features as well. You can use a light table to analyze period photo imagery from a reconnaissance aircraft, learn how a synchronizer allowed machine gun bullets to miss propeller blades, and take the controls of a Sopwith Camel to experience the sounds of this highly maneuverable fighter. An immersive exhibit on trench warfare at first seems rather two dimensional. However, a look through trench periscopes provides some basic context on the infantryman’s view of aviation.

Snoopy first imagined himself flying his doghouse in 1965. Through the comic pages, as well as books, games, cartoons, and toys, Snoopy has been a consistent reminder of World War I aviation.

At the beginning of the war in the Summer of 1914, the airplane was still a novel invention, a little more than a decade old. Very few aircraft were designed for any military purposes. As the war progressed, rudimentary flying machines quickly became faster, more maneuverable and better armed.

Airplanes were also needed on a large scale. Over 215,000 aircraft were built between 1914 to 1918. A myriad of new products were developed or adapted for use in aviation such as specialized cameras, radios, and aerial bombs. Many items first developed in World War I are still used in modern aviation, like the artificial horizon instrument, flight suits, and oxygen masks to name just a few. This sudden and sustained demand for combat aircraft and accessories gave rise to a new industry filled with highly skilled workers, an industry we rely on today.

American, British and French propellers

Although World War I ended over a century ago, its impact is still very much felt today. World War I, the Birth of Military Aviation provides valuable insight into an important but not altogether well understood period in the history of aviation. The gallery’s opening is also an important and welcome step toward the completion of NASM’s comprehensive, multi-year renovation.

* * *

Route Recon

The Smithsonian Institute’s National Air and Space Museum (NASM) is located on the National Mall bordered by Independence Avenue, Jefferson Drive, and 4th and 7th Streets, SW. The entrance is on the north side of the building facing the National Mall. You cannot access the museum from the south side along Independence Avenue. Free timed tickets are required for entry into NASM. Tickets can be acquired through the NASM website. Ticket holders will line up near the entrance on the Mall side of the Museum building prior to their entrance time. Entry prior to the time on the ticket is not allowed, but ticket holders can enter after the ticket time.

Parking – Very limited metered street parking is available around the museum. Parking is available in several commercial parking lots in the neighborhood.

Public Transportation

Metrorail – The closest Metro station is L’Enfant Plaza, along the blue, orange, silver, and green lines. From the L’Enfant Plaza Station, take the exit for Maryland Avenue and 7th Street.

Metrobus – Bus stops are located on Independence Avenue, SW, and along 7th Street, SW. Visit the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority for more information.

Command Reading

Capt. Arthur Ray Brooks, America’s Quiet Ace of W.W.I by Walter A. Musciano – Originally published in 1963, Musciano’s concise work provides a brief overview of Brooks’ life with some straightforward accounts of World War I aerial combat. It also includes an interesting assortment of historic World War I photographs of Brooks and his fellow aviators as well as detailed informaton on the aircraft Brooks flew.