On a hot summer day, five authentically dressed men reenact a 19th century US Army artillery detail. The solider in charge of the detail, or gunner, calls the commands while the cannoneers crisply and meticulously execute the drill. The highly polished barrel of the M1841 mountain howitzer shines brightly in the sun. The gunner shouts the final command: Fire! A cannoneer pulls the lanyard, a spark ignites the powder charge within the cannon. Brilliant flashes of flame shoot from the breech of the cannon’s barrel. Booms echo off the brick walls while smoke fills the sultry air.

National Park Service volunteers reenact a 19th century cannon drill at Fort Washington.

The reenactors are National Park Service volunteers demonstrating the skills of artillery soldiers at Fort Washington Park in suburban Prince George’s County, Maryland, just east of Washington, DC. Mention Fort Washington Park to an area resident and you are likely to get a blank stare or a vague reference to the local neighborhood of the same name. Many are unaware of this national park, hugging the eastern shore of the Potomac River just south of Alexandria, Virginia. Indeed, a recent sunny day found mostly local residents visiting the park, jogging, walking dogs and biking along the park’s avenues and trails.

The story of Fort Washington is really the story of four different forts spanning almost 140 years. The first three of which were built specifically to defend Washington, DC from an enemy naval attack via the Potomac River. In today’s era of jet aircraft and precision guided missiles, we do not think much about coastal defense. Yet in the first 150 years of the United States, it was an important strategic and sometimes political issue.

The Fort Washington Park Visitor Center building was originally the post commander’s quarters. It dates from 1822.

The Fort Washington Park Visitor Center is the worthwhile first stop for new visitors to Fort Washington. Housed in the original post commander’s quarters, the visitor center provides helpful background on how America’s approach to coastal defense changed through history. Displays detail nearly 140 years of Army life at Fort Washington, describing the four different forts, the various weapons deployed as well as the different Army units posted here. Make sure to step out onto the back deck. The commanding views of the Potomac River reveal why this location was selected for Washington, DC’s defense.

Near the visitor center, two concrete relics are reminders of the “third” Fort Washington. After the Civil War, the world’s navies began building warships with iron and steel, rather than wood. In the 1880’s, the Army developed the Endicott System for coastal defense which included concrete structures and rifled guns and other armaments that could penetrate the armored plating of these new combat vessels.

The present day ruins of Decatur Bunker.

Between 1891 and 1902 the Army built a series of eight concrete bunkers around Fort Washington to position these weapons. Adjoining the parking lot is Decatur Bunker. While today is looks like a set for a post-Apocalyptic movie, it was originally built to house two 10-inch “disappearing guns” named because the cannons would drop down behind the bunker wall after firing, allowing for safe reloading.

The bunkers were electrified and had telephones connected to a central tower where an officer directed the fire of the batteries as necessary. The Fire Control Tower is located right next to the visitor center. Although the bunkers are visible, they are fenced off and entry is prohibited. However, similar Endicott System bunkers across the Potomac River at nearby Fort Hunt in Virginia are open for public exploration.

The Fire Control Tower

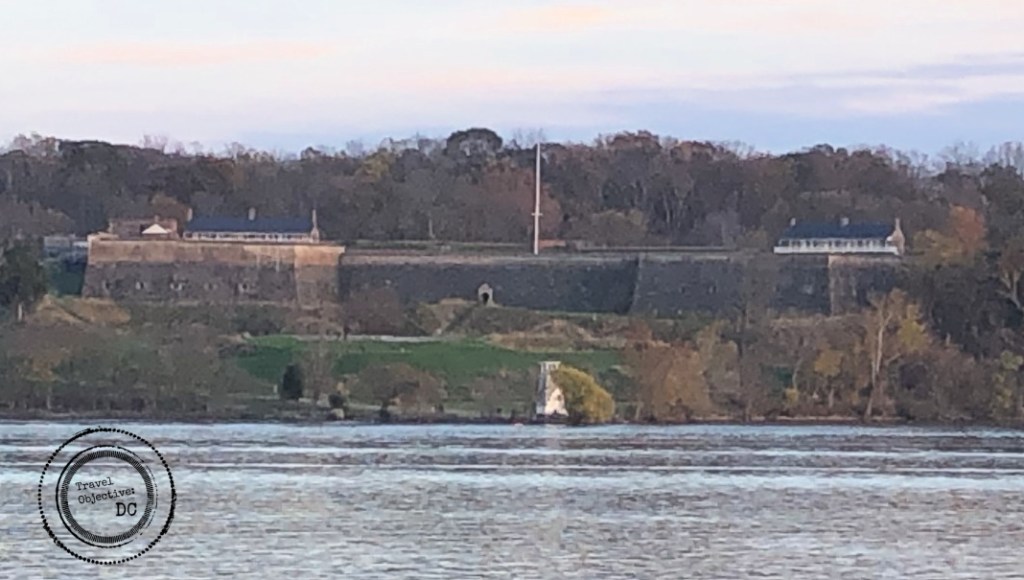

A short walk from the visitor center is the “second” Fort Washington, the main attraction at Fort Washington Park today. Built after the War of 1812, it was finished in 1824, but largely unused until a renovation in the 1840’s allowed the fort to be sufficiently armed.

Approaching the main gatehouse with a dry moat and large drawbridge, the fort feels almost medieval. But it really is the product of careful military engineering reflecting the defensive technology and combat tactics of the time. The fort is distinctive as one of the few remaining coastal fortifications in its original form.

Designed to thwart attacks by land as well as by water, the fort’s massive brick walls have many angles and turns so defending solders could have multiple positions to fire on attackers. Parapets on the western wall facing the river provided firing positions for the sizable cannons to engage enemy ships. Several types of cannons in use at the fort are on display, including an original 24-pounder cannon so named because the solid cannonballs it fired weighed 24 pounds (with a range of 1900 yards)!

A large parade field dominates the interior of the fort. The parade field was a center of daily life for the soldiers. Here troops would parade, stand inspections, answer daily roll calls, organize work parties, and conduct drills. Adjoining the parade field are two long brick buildings, one housed officers and their families, the other was the enlisted barracks.

A left turn down the hill from the fort’s main gate leads to the river and an area known as Digges Point. In the century before the Army built fortresses on this ground, the Digges family, transplants from Virginia, maintained a tobacco plantation named Warburton on today’s parkland. Thomas Digges was a contemporary and friend of his neighbor George Washington. George and Martha Washington regularly visited Warburton, traveling by riverboat from Mount Vernon and disembarking at Digges Point. A US Coast Guard channel marker stands in the area today.

As concern about another war with Britain continued growing in the early 1800’s, Congress allocated money for a system of fortifications to protect the Eastern Seaboard. The Army built the first fort near Digges Point in 1809. Originally known as Fort Warburton, it had 14-foot-high brick walls and up to 26 cannons.

Unfortunately, Fort Warburton did not fare well in its first and only engagement. On August 27, 1814, a ten ship Royal Navy flotilla sailed up with Potomac River towards Alexandria. A day earlier, Washington, DC had been attacked and burned by other British forces. With only enough soldiers to crew five cannons, and sensing defeat, the fort’s commander, Captain Samuel Dyson took drastic action.

He ordered the cannons be destroyed, the magazine with all its black powder blown up, and the garrison to withdraw. The magazine’s explosion left most of the fort heavily damaged before Royal Navy guns destroyed the rest. Not surprisingly, Captain Dyson’s chain of command considered this a very poor decision. He was courtmartialed and dismissed from the Army. There is not much of the original fort remaining today, but its original location on a grassy, level piece of ground near Digges Point is evident.

The introduction of the airplane in World War I made the idea of large forts with cannon for coastal defense obsolete. In the decades following the war, the fourth Fort Washington served as a garrison for the 3rd Battalion, 12th Infantry Regiment, the Army’s ceremonial unit (a role played by the 3rd Infantry Regiment today). During World War II, the Adjutant General Corps located its training school at Fort Washington and the 67th Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps detachment also called it home.

There are few remaining buildings from this time. In 1946, Fort Washington was turned over to the Department of the Interior to become a national park and over 300 buildings were removed.

This brick building served as a post exchange and gymnasium. It is one of the few surviving buildings at Fort Washington from the 20th Century.

With the soldiers long departed, Fort Washington’s mission today is to provide a place for recreation. Beyond history, the park’s expansive green spaces and proximity to the water provide a unique natural setting. Several walking trails traverse the grounds with varied habitats. Bird and wildlife are abundant. Watch for deer, foxes, and raccoons. In the open areas, a variety of songbirds can be observed while bald eagles, osprey, herons, and mallards are seen along the river. Fishing is an option as well with dozens of fish species in the adjoining waters.

While the Washington region teams with many significant sites in US military history, Fort Washington is unique. Where other sites are related to a single event or era, Fort Washington chronicles the period from wooden ships to World War II. A “must see” for those interested in defensive fortifications, Fort Washington is also a most pleasant place to spend some quiet time on the Potomac River. So, pack a picnic, bring your binoculars for the views, and walk through some history at Fort Washington.

* * *

Route Recon

The Fort Washington Park Visitor Center and the historic fort are open Thursday – Sunday from 9:00 am – 4:30 pm, except on Christmas and New Year’s Day. The Visitor Center and historic fort are closed on Monday, Tuesday and Wednesday.

The park grounds are open through sunset each day. From October – April, park grounds open at 8:30 am. From May – September, park grounds open at 6:30 am.

Fort Washington hosts living history as well as conservation programs on a recurring basis. Check the Fort Washington Park website for more information and schedules.

There is no charge to visit Fort Washington.

A State of Maryland fishing license is required to fish at Fort Washington.