On July 15, 1944, Staff Sergeant Kazuo Otani and his unit Company G, 2nd Battalion, 442nd Regimental Combat team were pinned down by enemy machine gun and sniper fire in a field near the Italian village of Pieve di Sante Luce in Tuscany.

The 442nd had arrived in Italy just three weeks prior and was part of the American advance against heavy German defenses.

Staff Sergeant Kazuo Otani of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team was awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions in Italy during World War II.

Otani’s unit objective was a hill adjoining the open field where his platoon was located. After killing one sniper, Otani repeatedly exposed himself to enemy fire while engaging multiple machine gun positions. Otani’s tactics provided cover for his platoon to maneuver. While preparing the platoon to assault the hill, one of his men was severely wounded. Otani ran back across the open field to render first aid, but was killed by an enemy machine gun blast.

Staff Sergeant Otani was ultimately awarded the Medal of Honor for his actions that day. His name, along with the names of more than 800 other Japanese American soldiers who were killed in action in World War II, is inscribed on a series of stone panels at a unique monument in Washington, DC.

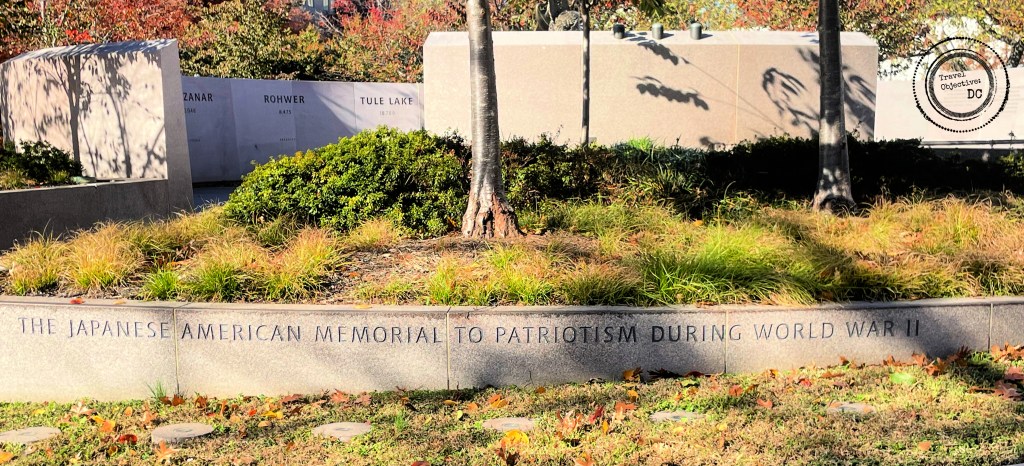

The Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in World War II is tucked into a 3/4 acre triangular space created by the intersection of D Street, New Jersey Avenue and Louisiana Avenue in Northwest Washington, DC, just north of the US Capitol.

The Reflecting Pool at the Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in World War II.

A large curved granite wall forms the perimeter around most of the memorial while the side facing Louisiana Avenue remains open, encouraging everyone passing by to enter the memorial’s space.

Opposite the memorial panels where the 800 names are inscribed is a reflecting pool. Within the pool are five large rough boulders representing the five generations of Japanese Americans impacted by World War II. Water from the pool gently flows down an angled edge, producing a calming background sound while carefully placed trees and bushes help to muffle the sounds of the bustling nearby neighborhood.

The centerpiece of the memorial is a tall bronze sculpture of two cranes. Their bodies mirror each other as they face opposite directions. Both cranes raise one wing high, the other kept low. A single strand of barbed wire wraps around them.

Cranes are featured prominently in the art and literature of East Asian cultures. In Japan especially, cranes are said to grant favors in return for acts of sacrifice.

The two cranes, bound by the wire, express the dual mission of this unique memorial: to recognize the heroric contributions of Japanese Americans on the battlefield while acknowledging the internment of tens of thousands Japanese Americans during the war.

A wreath laid in honor of Veterans Day

Three engraved stones by the memorial’s entrance nearest the crane statue provide helpful historical context.

Shortly after the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 directing the internment of Americans of Japanese ancestry. Ultimately, over 120,000 people were incarcerated under harsh conditions in camps located in the American west and south.

Encircling the crane statue are ten large stone panels each depicting the name of one of those camps and the number of people detained there. Many internees would remain at these facilities until March 1946. Other wording along the memorial’s walls includes quotes from Japanese American writers, veterans and Presidents Truman and Reagan.

Mike Masaoka of Fresno, CA was a longtime advocate for the Japanese American community as well as a soldier in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team.

While initially excluded from military service, younger Japanese Americans eagerly enlisted once allowed. The men served primarily in several segregated units, such as the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the 1399th Engineer Construction Battalion.

Some joined the Military Intelligence Service. Serving in the Pacific Theater, these soldiers used their language capabilities in many ways. They landed on beaches with invasion forces to capture enemy documents, deployed on special operations behind enemy lines, and interrogated prisoners.

After November 1943, Japanese American women were allowed to join the military as well. They served within the Women’s Army Corps, often working as linguists. Others became nurses.

U.S. Fifth Army soldiers of Company M, 100th Infantry Battalion, 442nd Regiment march through Vada, Italy, to an area where Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark would present the Presidential Citation for outstanding action in combat to the 100th Infantry Battalion, which was composed of Japanese-American troops.

– US Army Photo

The 442nd Regimental Combat Team with the attached 100th Infantry Battalion fought together in Europe, initially in Italy, then Southern France and later Germany.

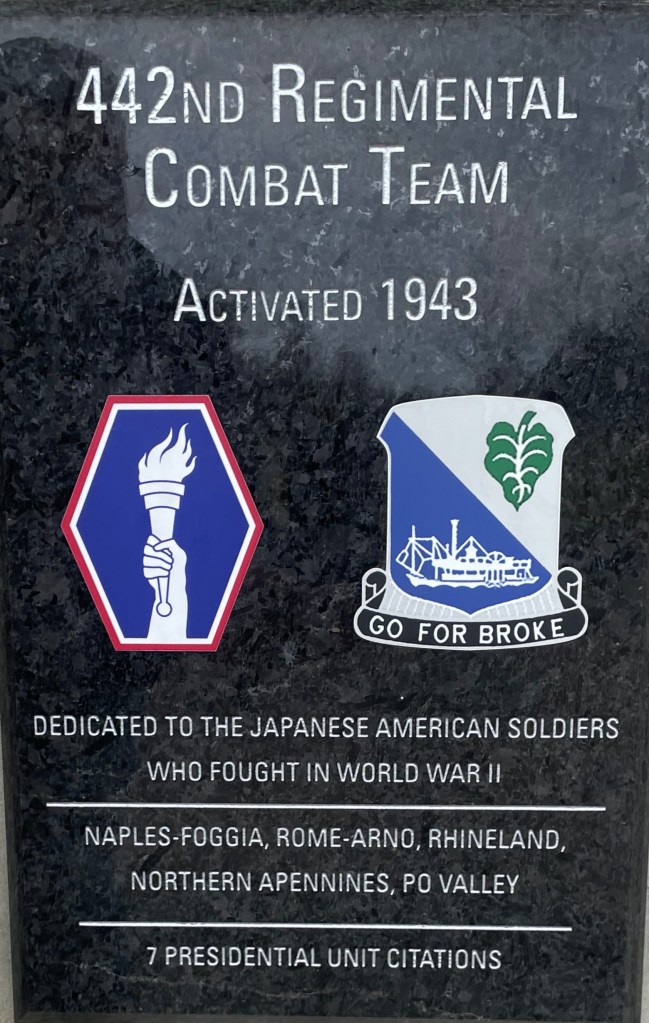

They repeatedly distinguished themselves in combat, becoming the most decorated military unit in US history for its size and duration of service. Soldiers of the unit earned over 18,000 individual decorations, including 4,000 Purple Hearts and 21 Medals of Honor. Collectively, the unit earned seven Presidential Unit Citations.

They truly embodied the regimental motto of Go for Broke.

A Unit Tribute Plaque dedicated to the 442nd Regimental Combat Team on display at the National Museum of the United States Army at Fort Belvoir, VA.

Decades after the final victory in 1945, the US Government took a series of steps to examine and reconsider the wartime internment of Japanese Americans.

In 1983, Congress appointed a special commission to review the language and implementation of Executive Order 9066. After several years of detailed research and over 700 interviews, the commission concluded in their final report that the relocation was based on “race prejudice, war hysteria and failure of political leadership” without any benefit to national security.

One of the commission’s recommendations was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan in 1988. The Civil Liberties Act, included a formal apology on the part of the US Government and pledged restitution to the former internees. Ultimately, in the early 1990’s most surviving internees would receive $20,000 in reparations.

President Ronald Reagan signs the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 into law.

That same year, the Go For Broke National Veterans Association Foundation, later renamed the National Japanese American Memorial Foundation, began the process of building a memorial in Washington, DC. In 1992, President George Bush signed legislation authorizing the building of the memorial on Federal land.

The memorial was formally dedicated on November 9, 2000.

In 2011, Congress collectively awarded the Congressional Gold Medal, its highest honor, on the soldiers of the 100th Infantry Battalion, the 442nd Regimental Combat Team and the Military Intelligence Service.

The Congressional Gold Medal honoring the Japanese American World War II soldiers who fought in the service of the United States

As is the case with most memorials in Washington, DC, the Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism in World War II can be sobering as well as inspirational. Upon a visit, one cannot help but reflect on the fragility of our Constitutional rights and need for vigilance in defending them.

At the same time, there is also a sense of resiliency of the human spirit, courage in the face of grave danger, and the importance of community in good times and bad.

The memorial also reminds us of the unfinished work undertaken by Sergeant Otani on that July day long ago and the need to continually tend to our task of building a more perfect union.

* * *

Route Recon

The National Japanese American Memorial to Patriotism During World War II is located at the intersection of New Jersey Avenue, Louisiana Avenue, and D Street in Washington, D.C. It is accessible 24 hours a day.

The closest Metrorail (subway) stop is Union Station. The memorial is a 10-15 minute walk from Union Station.

The National Japanese American Memorial Foundation hosts a number of events at the memorial and around the area to commemorate the history and contributions of Japanese Americans. See their website for more information.

Further details on the Congressional Gold Medal honoring the Japanese American soldiers of World War II soldiers can be found at this Smithsonian Institute website.