Along 7th Street in Northwest Washington, a narrow staircase takes the visitor up two flights to a suite of simple rooms restored to resemble their 19th Century appearance.

Today these rooms are often quiet, save for the tours and visitors. But from 1865 through 1868, they bustled with an extraordinary initiative led by Clara Barton. The noted humanitarian undertook the challenging but critically important mission of identifying missing Union solders from the Civil War.

By 1865, the former teacher and Patent Office clerk had already made a name for herself. She spent the Civil War years gathering and distributing medical supplies, food and other items for the Union Army. At the same time, she assisted soldiers, nursing the sick and wounded, and comforting all those she could.

A photograph of Clara Barton by Mathew Brady

-Library of Congress

After the war, she became aware of the large volumes of mail arriving at Army facilities either addressed to missing soldiers or seeking information on their whereabouts. Sadly, most of these letters went unanswered. At the time, the Army had no system for notifying a family upon the death or absence of a soldier.

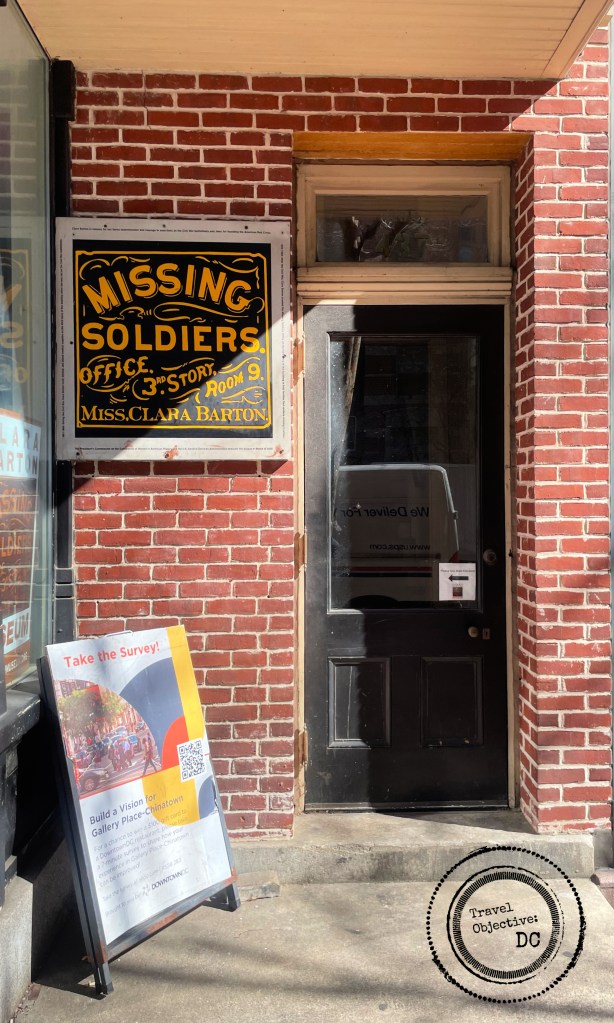

After receiving the endorsement of President Lincoln, Barton undertook the work of identifying as many of the Union Army missing as possible. She established the Office of Correspondence with Friends of the Missing Men of the United States Army, which would later become known more simply as the Missing Soldiers Office.

Barton based the operation on the third floor of a building then located at 488 1/2 7th Street Northwest. Originally built in the 1850’s, the three story brick building was of a typical design for Washington, DC. The first floor was dedicated to retail space along busy 7th Street. The second floor usually provided office space to local professionals while boarders rented rooms on the third floor.

The staircase to the 3rd Floor at the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum

Barton first rented a third floor room to lodge in and store some medical supplies in June of 1861. However, the Missing Soldiers Office would require more space. She rented additional rooms from her friend and landlord Edward Shaw, a co-worker from the Patent Office.

Today there are nine rooms on display as part of the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum. The dimly lit rooms have pretty wallpaper, but are largely empty. Creaks emanating from the uneven hardwood floors add a sense of authenticity to the space. Each room has some period furnishings and a few artifacts on display.

Much of the work of the Missing Soldier’s Office was performed in a large room facing 7th Street. Originally three rooms, Barton and Shaw continued to expand the office my removing walls to accommodate the growing staff and workload. The room’s location made it a natural choice to be the principal working area as the westward facing windows fill the room with natural light, in contrast to the other dimly lit areas. An artist’s depiction shows what the room may have looked like with racks for storage of supplies and large tables for reading and responding to correspondence.

The original door to Room 9 of the Missing Soldiers Office. Note the mail slot on the lower left, cut into the door by Clara Barton.

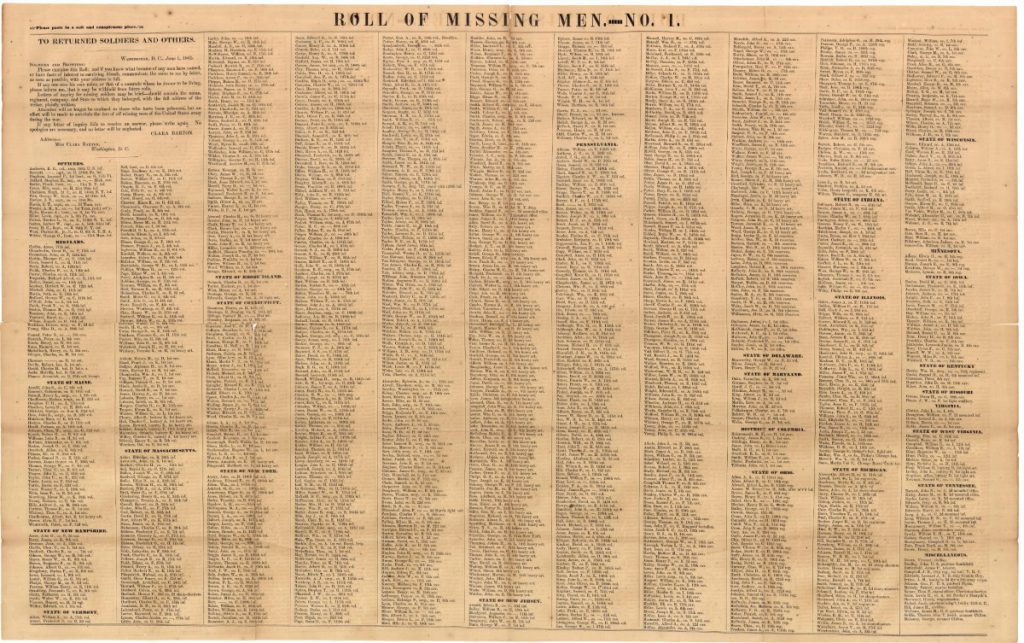

Barton implemented a straight forward and highly effective system for gathering information about the missing. After she received letters regarding the whereabouts of a missing soldier, a file was created. The names of the missing, organized by state of origin, were compiled into large lists called a Roll of Missing Men.

These rolls were printed on large broadsheet paper and distributed nationwide. They were hung prominently in post offices, government buildings and other public gathering places. The names were also published in newspapers. Returning soldiers or anyone with any information about a name on the list was invited to write the Missing Soldiers Office. Incoming letters were analyzed and collated into the files in the hopes of ultimately identifying the soldier’s fate.

A Roll of Missing Men. Clara Barton had these large lists printed and distributed nationwide.

-Photo courtesy of the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum

Barton and her staff collected and scrutinized any available records from prisons, hospitals, and burial sites. Former prisoners of war were also interviewed and proved to be excellent sources of information.

Barton had some early success in her work when she met a young solider named Dorence Atwater. Atwater had been a prisoner at the notorious Andersonville prison camp in southern Georgia where he kept the camp records on the burials of deceased Union prisoners. He also secretly kept a second list of burial information, which he smuggled out of the prison at war’s end.

Atwater and Barton accompanied an Army visit to Andersonville in the summer of 1865. Using Atwater’s list and other records, troops replaced temporary, numbered grave markers with more permanent headboards listing the solders names and units. While this work was underway, Barton and Atwater responded to letters with the updated burial information. Ultimately, Barton and Atwater were able to identify the graves of all but 450 of the 13,000 Union soldiers who had died at Andersonville.

A photograph of Dorence Atwater taken around 1870

-Connecticut State Library

One of the other rooms on the third floor served as Clara Barton’s bedroom, another as Shaw’s. Barton also decorated one room as a parlor where she would receive visitors. Receiving and responding to correspondence was only a portion of her role in the Missing Soldiers Office. Barton financed most of the operation herself, so she was often busy talking to donors and lobbying Congressmen. Of course, family members, those offering information, Army officials and others with an interest in her work would regularly call upon her on the 3rd floor.

As Barton wrote in her diary “…I was to leave everything else and fit up my little parlor with its cabinet of relics…I must see people if I would get their interest and I must have a suitable place to see them in…”

Barton closed the Missing Soldiers Office in late 1868. Incoming correspondence had slowed and she was suffering from exhaustion. But the results of the years long effort were most impressive. The Missing Soldier’s office received over 63,000 letters of inquiry and responded to over 42,000. It distributed over 99,000 Rolls of Missing Men and helped to identify over 22,000 soldiers.

Additionally, when Barton and her staff could positively identify a missing soldier, their letter to the family was official government correspondence. It could be used as supporting documentation for a death benefit application. As such, these letters could provide a route to material support as well as emotional consolation.

After closing the office, Barton traveled to Europe on her doctor’s advice. She visited a friend’s family in Geneva, Switzerland. While there, Barton was first exposed to the Geneva Convention and the work of the International Committee of the Red Cross. The next chapter of her life was waiting, and she did not look back.

Photograph of Boyce and Lewis Shoe Store at 437 7th Street. The facade hides the original brick exterior and several windows on the 2nd and 3rd floors.

-Library of Congress

In Washington, Shaw closed the previous chapter of her life. After she left for Europe, he packed up some of her personal belongings along with a mix of other materials from the third floor and placed them in the attic. He would live on the third floor a few more years, before moving on. Other boarders would come and go. In 1913, the third floor was sealed off from the rest of the building. The Missing Soldier’s Office became a bit of a footnote, a brief interlude in Barton’s life.

Just before Thanksgiving in 1996, a General Services Administration carpenter named Richard Lyons was inspecting the building before its scheduled demolition. While examining the unused 3rd floor, he discovered the trove of artifacts stored 120 years earlier, including the now iconic Missing Soldiers Office sign.

When a GSA carpenter discovered the Missing Soldiers Office sign in the attic, he knew he had found something significant.

Lyons began a research project that ultimately saved the building and an extensive renovation followed. The space is currently administered by the National Museum of Civil War Medicine, which partnered with the GSA in the renovation space. The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Museum was opened to the public in 2015.

Today, a visit to the museum feels like a step back in time. The first floor, which for decades was used as a shoe store, is an open reception area housing the gift shop along with a large mural depicting the life of Clara Barton.

Reproduction wallpaper hangs in a room at the Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Museum. Curators conducted extensive research on the original wallpaper samples still available to recreate the look of the rooms in Barton’s time.

Extensive research has been done on returning the rooms to their 19th Century appearance, especially the wallpaper. Barton favored bold floral patterns for her personal space, office spaces had more muted colors in geometric designs.

A selection of artifacts is on display through the rooms, including receipts, pens, stationery packaging, old clothing, and most impressive, a copy of the first Roll of Missing Men.

Today, of course, Barton’s work would not be necessary. The US Military has a very organized system for notifying next of kin about the loss of a service member. DNA samples are taken and stored to aid in identification. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency works to identify the missing from earlier wars and conflicts.

But before these systems were in place, it was a visionary Clara Barton who saw the need and created a structure to meet it. To make it work, she raised money, traveled the country giving speeches, lobbied Congress, issued reports, sought assistance from other Federal agencies and directed an extensive program of correspondence and outreach.

It all happened over 150 years ago on 7th Street. Climb the stairs and see for yourself.

* * *

Route Recon

The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Musuem is located at 437 7th Street NW, Washington, DC 20004. The museum is open on Fridays and Saturdays from 11:00 AM to 5:00PM. The nearest Washington Metro Station is Archives-Navy Memorial-Penn Quarter. From the station exit, make a U-Turn back toward 7th Street. Turn left on 7th Street and proceed past D Street. The Clara Barton Missing Soldiers Office Musuem will be on your right just before E Street.

Command Reading

Relics of War, the History of a Photograph by Jennifer Raab

In 1865, on her visit to Andersonville, Clara Barton collected a variety of small artifacts she found around the camp, such as dug out bowls and cups, woven reed plates and spoons made from animal horns. She arranged these pictures on a writing desk and had them photographed. Barton used the relics in her work to raise awarness and enthusiasm for her Missing Soldiers Office and its mission. In her book, Dr. Raab, a professor of the history of art at Yale University, uses artistic criticism techniques to interpret the photograph and what it came to mean for post Civil War American society.